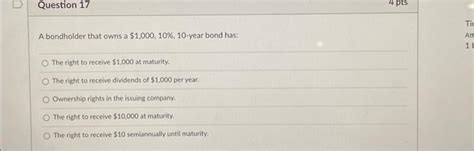

A Bondholder That Owns A $1000 10 10-year Bond Has:

Breaking News Today

Apr 01, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

A Bondholder Owning a $1,000, 10%, 10-Year Bond: A Deep Dive into Ownership and Returns

A bond is essentially a loan you make to a government or corporation. In return for lending your money, the borrower agrees to pay you back the principal (the initial amount you lent) at a specified date (maturity date) and to make regular interest payments during the life of the bond. Let's explore the implications of owning a $1,000, 10%, 10-year bond. This detailed analysis will cover various aspects, from initial investment and interest payments to potential risks and overall returns.

Understanding the Bond's Characteristics

Before diving into the specifics of ownership, let's dissect the characteristics of this hypothetical bond:

-

Principal (Face Value or Par Value): $1,000. This is the amount the bondholder will receive back at maturity.

-

Coupon Rate: 10%. This is the annual interest rate the bond pays.

-

Maturity Date: 10 years. This is the date when the principal is repaid.

-

Annual Interest Payment: The annual interest payment is calculated as 10% of the face value: $1,000 * 0.10 = $100. This means the bondholder receives $100 every year for ten years.

-

Semi-Annual Interest Payments: While the coupon rate is quoted annually, interest payments are typically made semi-annually. This means the bondholder receives two payments of $50 ($100/2) each year.

The Bondholder's Perspective: Year-by-Year Breakdown

Let's follow the bondholder's experience year by year:

Year 1: The bondholder receives two payments of $50 each, totaling $100 in interest. The principal remains at $1,000.

Year 2: Two more payments of $50 each ($100 total) are received. The principal remains at $1,000.

Year 3 - Year 9: This pattern continues for the remaining years. The bondholder receives $100 annually in interest, with the principal remaining untouched at $1,000.

Year 10 (Maturity): At the end of the tenth year, the bondholder receives the final interest payment of $100, and crucially, the full principal of $1,000 is repaid.

Total Return on Investment

Over the 10-year period, the bondholder receives a total of $1,000 in interest payments ($100/year * 10 years) plus the return of the initial $1,000 principal. Therefore, the total return is $2,000. This represents a significant return on the initial investment.

Factors Affecting Bond Value: Market Fluctuations

While the bond promises a fixed return at maturity, its value can fluctuate in the secondary market before maturity. Several factors influence this:

-

Interest Rate Changes: If prevailing interest rates rise, newly issued bonds will offer higher yields. This makes existing bonds with lower coupon rates less attractive, reducing their market value. Conversely, if interest rates fall, the existing bond becomes more attractive, increasing its market value. This is known as interest rate risk.

-

Credit Rating Changes: The creditworthiness of the issuer (government or corporation) significantly impacts bond value. A downgrade in the credit rating (e.g., from AAA to AA) signals increased default risk, leading to a decrease in bond price. Conversely, an upgrade increases the bond's value. This is known as credit risk.

-

Inflation: Unexpectedly high inflation erodes the purchasing power of the future interest and principal payments, impacting the real return of the bond. This is known as inflation risk.

-

Market Sentiment: General economic conditions and investor sentiment can also influence bond prices. During periods of economic uncertainty, investors might favor safer assets like government bonds, driving up their prices.

Calculating Yield to Maturity (YTM)

Yield to maturity (YTM) is the total return an investor can expect if they hold the bond until maturity. It accounts for the interest payments and the difference between the purchase price and the face value. If the bond is purchased at its face value ($1,000), the YTM equals the coupon rate (10%). However, if the bond is bought at a discount or premium, the YTM will differ from the coupon rate. For example:

-

Purchased at a discount: If the bond is purchased for less than $1,000, the YTM will be higher than 10% because the investor receives a greater return on their initial investment.

-

Purchased at a premium: If the bond is purchased for more than $1,000, the YTM will be lower than 10% because the investor pays more upfront for the future interest and principal payments.

Risks Associated with Bond Ownership

While bonds are generally considered less risky than stocks, they still carry certain risks:

-

Default Risk: The issuer might fail to make interest payments or repay the principal at maturity. This risk is higher for corporate bonds than for government bonds.

-

Reinvestment Risk: If interest rates fall after purchasing the bond, the interest payments received might be difficult to reinvest at a comparable yield.

-

Inflation Risk: As mentioned, inflation can erode the real value of the bond's returns.

-

Liquidity Risk: Bonds might not be easily sold in the secondary market, especially less liquid bonds.

Diversification and Portfolio Management

Owning a single bond, regardless of its characteristics, is generally not advisable. Diversification across different bond types (government, corporate, municipal), maturities, and issuers is crucial to mitigate risk. Including bonds in a diversified portfolio alongside stocks and other asset classes helps reduce overall portfolio risk and enhance returns.

Comparing Bonds to Other Investments

Bonds offer a different risk-return profile compared to other investments like stocks. Stocks generally offer higher potential returns but also come with greater volatility and risk. Bonds are considered less volatile but also offer lower potential returns. The optimal allocation between bonds and stocks depends on individual risk tolerance and investment goals.

Tax Implications

Interest income from bonds is typically taxable. The tax rate depends on the type of bond and the investor's tax bracket. Municipal bonds, issued by state and local governments, often offer tax-exempt interest income, making them particularly attractive for investors in higher tax brackets.

The Role of a Bondholder in Corporate Governance

While bondholders are primarily creditors, they often have some degree of influence on the issuer's actions, especially in the case of corporate bonds. Bondholders' agreements might include covenants that restrict the issuer's actions to protect their investment. In cases of financial distress, bondholders may have a say in the restructuring process.

Conclusion: A Balanced Perspective on Bond Ownership

Owning a $1,000, 10%, 10-year bond offers a relatively predictable stream of income and a guaranteed return of principal at maturity. However, it's vital to understand the risks associated with bond ownership and to diversify investments to mitigate those risks. The decision to invest in bonds should be made after careful consideration of individual risk tolerance, investment goals, and a comprehensive understanding of the market dynamics impacting bond prices. Remember, this analysis provides a simplified view; professional financial advice should always be sought before making any significant investment decisions.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Which Scenario Best Explains The Process Of Assimilation

Apr 02, 2025

-

Are Evidence Of Disease Sensed By The Sick Person

Apr 02, 2025

-

Mechanical Abrasions Or Injuries To The Epidermis Are Known As

Apr 02, 2025

-

Which User Has Access To The Voided Deleted Transactions Tool

Apr 02, 2025

-

What Work Was Installed In The Pantheon In Paris

Apr 02, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about A Bondholder That Owns A $1000 10 10-year Bond Has: . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.