A Chemical Reaction Has Reached Equilibrium When

Breaking News Today

Mar 12, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

A Chemical Reaction Has Reached Equilibrium When… The Dynamic Balance of Nature

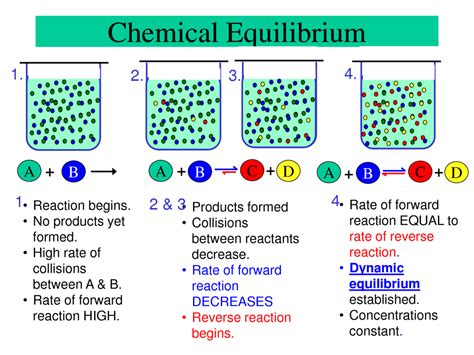

Chemical equilibrium is a fundamental concept in chemistry, crucial for understanding countless natural processes and industrial applications. It's a state of dynamic balance, not a static standstill, where the rates of the forward and reverse reactions are equal. This means that while the concentrations of reactants and products remain constant, the reactions themselves are still occurring. Understanding when and how a reaction reaches equilibrium is key to predicting its behavior and manipulating its outcome.

Defining Chemical Equilibrium: A State of Dynamic Balance

A chemical reaction reaches equilibrium when the rate of the forward reaction equals the rate of the reverse reaction. This doesn't mean the reaction has stopped; instead, it signifies a balance between the formation of products and the reformation of reactants. Imagine a busy highway with equal numbers of cars traveling in both directions. The overall number of cars at any given point on the highway remains relatively constant, even though cars are constantly moving. Equilibrium is similar – the concentrations of reactants and products remain constant, despite the ongoing reactions.

Key Characteristics of Equilibrium:

- Constant Concentrations: The concentrations of reactants and products remain unchanged over time.

- Dynamic Nature: The forward and reverse reactions are still occurring at equal rates.

- Reversible Reactions: Equilibrium is only possible in reversible reactions, reactions that can proceed in both forward and reverse directions.

- Closed System: Equilibrium is usually observed in closed systems, where there is no exchange of matter with the surroundings. If matter is added or removed, the equilibrium will shift.

The Equilibrium Constant (Kc): A Quantitative Measure

The equilibrium constant, denoted as Kc, is a quantitative measure of the relative amounts of reactants and products at equilibrium. For a general reversible reaction:

aA + bB ⇌ cC + dD

The equilibrium constant expression is given by:

Kc = ([C]^c [D]^d) / ([A]^a [B]^b)

where [A], [B], [C], and [D] represent the equilibrium concentrations of the respective species, and a, b, c, and d are their stoichiometric coefficients.

A large Kc value (Kc >> 1) indicates that the equilibrium lies far to the right, meaning that the products are favored at equilibrium. Conversely, a small Kc value (Kc << 1) indicates that the equilibrium lies far to the left, favoring the reactants. A Kc value close to 1 indicates that the concentrations of reactants and products are comparable at equilibrium.

Factors Affecting Equilibrium: Le Chatelier's Principle

Le Chatelier's principle states that if a change of condition is applied to a system in equilibrium, the system will shift in a direction that relieves the stress. These changes can include:

1. Changes in Concentration:

Adding more reactants will shift the equilibrium to the right, favoring product formation. Conversely, adding more products will shift the equilibrium to the left, favoring reactant formation. Removing reactants or products will have the opposite effect.

Example: Consider the Haber-Bosch process for ammonia synthesis:

N₂(g) + 3H₂(g) ⇌ 2NH₃(g)

Adding more nitrogen or hydrogen will shift the equilibrium to the right, increasing the yield of ammonia. Removing ammonia as it is formed will also shift the equilibrium to the right, further increasing the ammonia yield.

2. Changes in Temperature:

The effect of temperature changes depends on whether the reaction is exothermic (releases heat) or endothermic (absorbs heat).

- Exothermic Reactions: Increasing the temperature shifts the equilibrium to the left, favoring reactants. Decreasing the temperature shifts the equilibrium to the right, favoring products.

- Endothermic Reactions: Increasing the temperature shifts the equilibrium to the right, favoring products. Decreasing the temperature shifts the equilibrium to the left, favoring reactants.

Example: The Haber-Bosch process is exothermic. Lowering the temperature favors ammonia production, but the reaction rate also slows down significantly. This is why a compromise temperature is used in industrial applications.

3. Changes in Pressure:

Changes in pressure only significantly affect equilibria involving gases. Increasing the pressure shifts the equilibrium to the side with fewer gas molecules. Decreasing the pressure shifts the equilibrium to the side with more gas molecules.

Example: In the Haber-Bosch process, there are 4 moles of gas on the reactant side (1 mole of N₂ and 3 moles of H₂) and 2 moles of gas on the product side (2 moles of NH₃). Increasing the pressure shifts the equilibrium to the right, favoring ammonia production.

4. Addition of a Catalyst:

A catalyst speeds up both the forward and reverse reactions equally. Therefore, adding a catalyst does not affect the position of equilibrium; it only affects the rate at which equilibrium is reached.

Applications of Chemical Equilibrium: From Industry to Nature

The principles of chemical equilibrium are essential in numerous applications across various fields:

1. Industrial Processes:

Many industrial processes, such as the Haber-Bosch process for ammonia synthesis, the contact process for sulfuric acid production, and the production of various metals, rely heavily on understanding and manipulating chemical equilibrium to maximize product yield and efficiency.

2. Environmental Chemistry:

Equilibrium principles play a vital role in understanding environmental processes, such as acid rain formation, the solubility of pollutants in water, and the distribution of chemicals in different environmental compartments.

3. Biochemistry:

Chemical equilibrium is crucial in understanding biochemical reactions, such as enzyme-catalyzed reactions and the regulation of metabolic pathways. The equilibrium constants of these reactions are often used to determine the direction and extent of biochemical processes within living organisms.

4. Medicine:

Equilibrium principles are essential in understanding drug distribution and metabolism within the body. The equilibrium between a drug's bound and unbound forms influences its effectiveness and potential side effects.

Distinguishing Equilibrium from Completion: A Crucial Difference

It’s important to differentiate chemical equilibrium from a reaction reaching completion. A reaction reaches completion when virtually all of the limiting reactant has been consumed and converted into products. In contrast, equilibrium involves a dynamic balance where both reactants and products coexist. The extent to which a reaction proceeds towards completion or equilibrium is determined by the reaction's equilibrium constant (Kc).

Determining the State of Equilibrium: Experimental and Theoretical Approaches

Determining if a reaction has reached equilibrium relies on both experimental and theoretical methods. Experimentally, we monitor the concentrations of reactants and products over time. When these concentrations cease to change significantly, it suggests equilibrium has been attained. Spectroscopic techniques, like UV-Vis or NMR, can be used to directly measure these concentrations.

Theoretically, we can predict the equilibrium position using the equilibrium constant (Kc) and the initial concentrations of reactants. By calculating the reaction quotient (Q), which has the same expression as Kc but uses instantaneous concentrations instead of equilibrium concentrations, we can compare it to Kc.

- Q < Kc: The reaction will proceed in the forward direction to reach equilibrium.

- Q > Kc: The reaction will proceed in the reverse direction to reach equilibrium.

- Q = Kc: The reaction is at equilibrium.

Calculating Q allows for a prediction of the reaction’s direction, providing valuable insights without necessarily needing to wait for equilibrium to be experimentally observed.

Conclusion: The Significance of Equilibrium in Chemistry and Beyond

Understanding chemical equilibrium is crucial for predicting the outcome of chemical reactions, optimizing industrial processes, and understanding various natural phenomena. The concept of dynamic balance, the equilibrium constant, and Le Chatelier's principle provide a powerful framework for comprehending and manipulating chemical systems, highlighting the significance of equilibrium in both theoretical chemistry and practical applications across diverse fields. Further exploration into specific reactions and their equilibrium properties allows for deeper insights into the complexities of chemical transformations and their influence on the world around us.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Match Each Phrase To The Cardiovascular System Function It Describes

May 09, 2025

-

What Does All Food Contact Equipment Need To Be

May 09, 2025

-

Plaster Or Gypsum Wall Covering On Interior Walls

May 09, 2025

-

A No Discharge Zone Restricts What Type Of Activity

May 09, 2025

-

Fahrenheit 451 Important Quotes And Page Numbers

May 09, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about A Chemical Reaction Has Reached Equilibrium When . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.