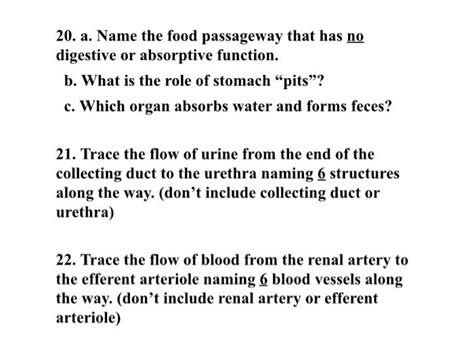

Food Passageway That Has No Digestive/absorptive Function

Breaking News Today

Apr 05, 2025 · 5 min read

Table of Contents

The Esophagus: A Food Passageway with No Digestive or Absorptive Function

The human digestive system is a marvel of biological engineering, a complex network of organs working in concert to break down food, absorb nutrients, and eliminate waste. While many organs within this system play active roles in digestion and absorption, one stands out for its remarkably singular function: transportation. This organ, the esophagus, is a muscular tube that serves as a crucial conduit for food, transporting it from the mouth to the stomach without contributing to the digestive or absorptive processes. This article delves into the fascinating anatomy, physiology, and clinical significance of the esophagus, highlighting its unique role in the digestive journey.

Anatomy of the Esophagus: A Muscular Passage

The esophagus, approximately 25 centimeters long in adults, is a collapsible, fibromuscular tube that begins at the level of the cricoid cartilage (in the neck) and extends through the thoracic cavity, piercing the diaphragm before connecting to the stomach at the gastroesophageal junction. Its anatomical position places it posterior to the trachea and anterior to the vertebral column in the neck and mediastinum.

Layers of the Esophageal Wall:

The esophageal wall comprises four distinct layers, each contributing to its overall function:

-

Mucosa: This innermost layer is a delicate lining made of stratified squamous epithelium, a type of cell specifically designed to withstand friction from the passage of food boluses. Unlike the stomach, the esophageal mucosa does not contain gastric glands responsible for acid and enzyme secretion. This lack of secretory glands underscores the esophagus's primary role as a conduit, not a site of digestion.

-

Submucosa: This layer beneath the mucosa contains blood vessels, lymphatics, and a network of nerves crucial for regulating esophageal motility. The absence of glands in this layer further reinforces the non-digestive nature of the esophagus.

-

Muscularis Externa: This is the thickest layer of the esophageal wall, consisting of two layers of muscle: an inner circular layer and an outer longitudinal layer. These muscles are responsible for the coordinated contractions known as peristalsis, which propel food down towards the stomach. The upper third of the esophagus contains striated (skeletal) muscle under voluntary control, allowing for conscious swallowing. The lower two-thirds consist of smooth muscle, controlled involuntarily by the autonomic nervous system.

-

Adventitia: The outermost layer, the adventitia, is a connective tissue layer that anchors the esophagus to surrounding structures.

Physiology of the Esophagus: The Mechanics of Swallowing

The act of swallowing, or deglutition, is a complex process involving coordinated actions of the mouth, pharynx, and esophagus. It's a crucial step in the food passageway, initiating the journey of food from the mouth to the stomach via the esophagus. The esophagus plays a passive role in the initial phases of swallowing but actively participates in the subsequent transport of the bolus.

Phases of Swallowing:

-

Oral Phase (Voluntary): This begins with the conscious act of chewing and forming a bolus of food. The tongue then propels the bolus posteriorly towards the pharynx.

-

Pharyngeal Phase (Involuntary): As the bolus enters the pharynx, the soft palate elevates to prevent food from entering the nasal cavity. The epiglottis closes over the larynx to prevent aspiration into the trachea. The upper esophageal sphincter (UES) relaxes, allowing the bolus to enter the esophagus.

-

Esophageal Phase (Involuntary): This is where the esophagus takes center stage. Once the bolus enters, a wave of coordinated muscle contractions (peristalsis) begins. These contractions propel the food bolus down the esophagus towards the stomach. The lower esophageal sphincter (LES), a ring of muscle at the gastroesophageal junction, relaxes to allow passage of the bolus into the stomach and then contracts to prevent reflux of stomach contents back into the esophagus.

Clinical Significance: Esophageal Disorders

Given its crucial role in food transport, esophageal dysfunction can significantly impact overall health. A range of disorders can affect the esophagus, impacting its structure and function.

Achalasia:

Achalasia is a motility disorder characterized by impaired relaxation of the LES and loss of peristalsis in the esophageal body. This results in difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), chest pain, and regurgitation of undigested food.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD):

GERD is a common condition caused by the weakening or dysfunction of the LES, leading to the reflux of stomach acid into the esophagus. This can cause heartburn, chest pain, and esophageal damage, such as esophagitis.

Esophageal Cancer:

Both squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma can occur in the esophagus. Risk factors include tobacco and alcohol use, Barrett's esophagus (a precancerous condition), and genetic predisposition.

Esophageal Diverticula:

These are outpouchings of the esophageal wall, often caused by weakened muscle. They can trap food and lead to infection or dysphagia.

Esophageal Strictures:

These are narrowings of the esophagus that can be caused by inflammation, scarring, or tumors. They can significantly impair swallowing.

The Esophagus in Comparative Anatomy: Variations Across Species

The esophagus, while fundamentally similar across vertebrates, demonstrates fascinating variations in structure and function reflecting dietary adaptations. For example, carnivores often possess a shorter, wider esophagus better suited for swallowing large food items. Herbivores may exhibit a longer, more convoluted esophagus to accommodate the digestion of plant matter. Birds, with their unique digestive systems, have a crop, an esophageal dilation that serves as a storage pouch for food before it enters the stomach.

Conclusion: A Simple Yet Vital Role

The esophagus, despite its seemingly simple function, is a critical component of the human digestive system. Its dedicated role in transporting food from the mouth to the stomach, without engaging in digestion or absorption, highlights the remarkable specialization and interdependence of the various organs involved in the digestive process. Understanding the anatomy, physiology, and potential pathologies of the esophagus is crucial for appreciating the intricate workings of the human body and for effectively diagnosing and treating related disorders. Further research into esophageal function and disease continues to yield important insights into improving patient outcomes and enhancing our understanding of this vital passageway.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

The Correct Detail Type For Account 115 Merchandise Inventory Is

Apr 05, 2025

-

An Oil Rig Searches For And Finds Oil Reservoirs

Apr 05, 2025

-

Manipulative Training Differs From Education And Training In That It

Apr 05, 2025

-

Rhetorical Devices In Letter From A Birmingham Jail

Apr 05, 2025

-

In Reference To Warrior Toughness Character Development Includes Toughness

Apr 05, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Food Passageway That Has No Digestive/absorptive Function . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.