Island Species Are Usually Most Closely Related To

Breaking News Today

Apr 01, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

Island Species Are Usually Most Closely Related To… Their Mainland Counterparts! The Intriguing Story of Island Biogeography

Islands, those isolated pockets of land surrounded by water, are biodiversity hotspots. They harbor unique species found nowhere else on Earth, often exhibiting remarkable adaptations to their specific environments. But where do these unique island species come from? The answer, more often than not, lies in their mainland relatives. Island species are usually most closely related to species found on the nearest mainland. This isn't just a hunch; it's a core principle of biogeography, the study of the geographical distribution of species and ecosystems.

The Basics of Island Biogeography: Colonization, Speciation, and Adaptation

Understanding the relationship between island and mainland species requires grasping the fundamental processes of island biogeography. These processes are intertwined and influence the evolutionary trajectory of island populations.

1. Colonization: The First Step

The journey of a species to an island begins with colonization. This typically involves dispersal, the movement of individuals from a mainland population to an island. Dispersal mechanisms vary greatly and depend on the species' traits and the distance to the island.

- Overwater dispersal: This is a crucial mechanism for many species. Birds, insects, and even reptiles can fly or be carried by wind currents to islands. Seeds and spores can be dispersed by wind or ocean currents.

- Rafting: Larger animals or plant fragments might be carried on floating debris, “rafting” across significant distances. This is particularly relevant for species adapted to coastal environments.

- Human introduction: Unfortunately, humans have played a significant role in introducing species to islands, often with detrimental consequences for native island biota.

The successful colonization of an island depends on factors like the distance from the mainland, the frequency of dispersal events, and the species’ ability to survive the journey and establish a new population. The closer the island is to the mainland, and the more frequent the dispersal events, the higher the likelihood of colonization.

2. Speciation: The Divergence of Island Populations

Once a species establishes a population on an island, it is isolated from its mainland ancestors. Over time, this isolation can lead to speciation – the formation of new and distinct species. Several factors contribute to speciation on islands:

- Genetic drift: In small, isolated populations, random fluctuations in gene frequencies can lead to significant genetic differences from the mainland population.

- Natural selection: The island environment often presents unique selective pressures, leading to adaptations that are not found in the mainland population. This could involve changes in morphology, physiology, or behavior.

- Reproductive isolation: The geographical isolation of the island population prevents gene flow with the mainland population, further enhancing divergence.

Over generations, these processes can lead to the formation of entirely new species that are endemic to the island, meaning they are found nowhere else.

3. Adaptation: The Shaping of Island Life

Island environments often present unique challenges and opportunities, leading to remarkable adaptations in island species. These adaptations can be morphological, physiological, or behavioral.

- Gigantism and dwarfism: Island gigantism, the evolution of larger body size in island populations, and island dwarfism, the evolution of smaller body size, are common phenomena. These size changes are often linked to the availability of resources and the absence of predators or competitors.

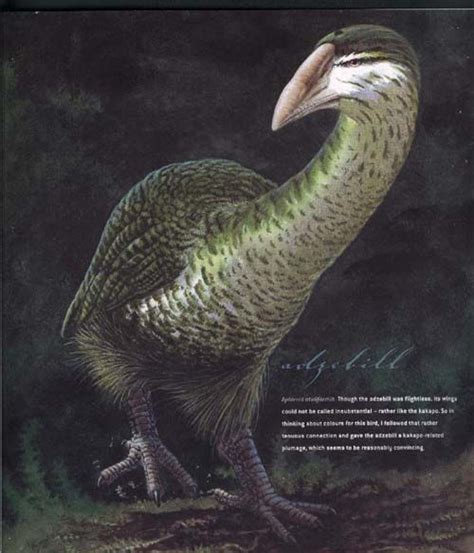

- Flightlessness: In the absence of predators, many bird species on islands have lost the ability to fly, investing energy in other traits like enhanced reproduction.

- Specialized diets: Island species often develop specialized diets adapted to the limited resources available on the island.

- Changes in coloration and behavior: These adaptations can help island species camouflage themselves, avoid predators, or attract mates in their unique environments.

The Evidence: Phylogenetic Studies and Molecular Data

The assertion that island species are closely related to mainland species isn't merely speculative. Decades of research, particularly using phylogenetic methods and molecular data, strongly support this claim.

Phylogenetic Analysis: Tracing Evolutionary Relationships

Phylogenetic analyses, which reconstruct evolutionary relationships between species based on shared characteristics, consistently show a close relationship between island species and their mainland counterparts. These analyses often use morphological data (physical characteristics) and genetic data (DNA sequences). By comparing these characteristics, scientists can build "family trees" that illustrate the evolutionary history and relationships among species. These trees regularly show that island species cluster closely with mainland populations, indicating a recent common ancestor.

Molecular Data: The DNA Tells the Tale

Molecular data, especially DNA sequences, provide even stronger evidence. DNA sequencing allows scientists to compare the genetic makeup of different species with high precision. The degree of genetic similarity between island and mainland populations reflects their evolutionary history. Generally, closely related species will share more similar DNA sequences than distantly related species. Studies consistently reveal that island species have a higher genetic similarity to their nearest mainland relatives compared to species on other continents or islands.

Case Studies: Illustrating the Mainland-Island Connection

Numerous examples illustrate the close relationship between island and mainland species.

Galapagos Islands: Darwin's Finches and More

The Galapagos Islands, famously studied by Charles Darwin, provide a compelling case study. Darwin's finches, with their diverse beak shapes adapted to different food sources, are closely related to finches found on the South American mainland. Similarly, other Galapagos species, like the Galapagos giant tortoise and marine iguanas, show close phylogenetic relationships to mainland relatives. The isolation on the Galapagos allowed these mainland colonists to radiate into diverse species that are unique to the islands.

Hawaiian Islands: An Archipelago of Endemism

The Hawaiian Islands, a volcanic archipelago in the central Pacific, are renowned for their high level of endemism. The diverse array of Hawaiian honeycreepers, with their specialized beaks adapted to different nectar sources, are descendants of a single mainland ancestor. Similarly, the unique Hawaiian silverswords, a diverse group of plants, trace their origin to a single ancestor from North America. The geographic isolation of the Hawaiian Islands has allowed the diversification of these lineages into a plethora of unique species.

The Mediterranean Islands: A Biodiversity Hotspot

The Mediterranean basin encompasses numerous islands that house a unique collection of flora and fauna. Many of these island species are closely related to those found on the nearby continents of Europe, Africa, and Asia. Their evolution has been shaped by the unique environmental conditions of the islands, leading to the striking adaptations observed in these species. These islands provide a perfect example of the interplay between isolation and adaptation in driving speciation.

Exceptions to the Rule: Long-Distance Dispersal and Ancient Origins

While the general rule holds true, there are exceptions. Some island species might show closer relationships to species located further away, hinting at long-distance dispersal events or ancient origins.

- Ancient lineages: Some island lineages might represent ancient colonizations that pre-date the current mainland populations. In these cases, the closest relatives might be extinct or located far away.

- Rare long-distance dispersal events: Some species might have dispersed across vast distances, leading to a closer relationship with a distant mainland population than their geographically closer neighbors.

- Incomplete sampling: Sometimes the phylogenetic analysis might be incomplete because we haven’t yet discovered all the relevant species or haven’t sampled sufficiently to find the closest relatives.

The Importance of Understanding Island Biogeography

Understanding the relationship between island and mainland species has profound implications for conservation biology. Island species are often highly vulnerable to extinction due to their small population sizes, limited genetic diversity, and susceptibility to invasive species. Knowing the evolutionary origins of island species helps prioritize conservation efforts and develop effective strategies for their protection. By understanding the processes of colonization, speciation, and adaptation, we can better manage and preserve the unique biodiversity found on islands worldwide. This knowledge is vital for maintaining the ecological balance of these fragile ecosystems and preventing the loss of irreplaceable species. Further research into island biogeography is crucial for developing robust conservation strategies, ensuring that these remarkable evolutionary narratives continue into the future.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

How Did Kuba Artists Decorate Their Ngady Amawaash Masks

Apr 02, 2025

-

A Research Study Using Naturalistic Observation Entails

Apr 02, 2025

-

When Both Partners Treat One Another With Matching Hostility

Apr 02, 2025

-

Which Of These Is Not An Option For Formatting Text

Apr 02, 2025

-

Label The Image With The Features Of Tectonic Plates

Apr 02, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Island Species Are Usually Most Closely Related To . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.