Meiosis Starts With A Single Diploid Cell And Produces

Breaking News Today

Mar 14, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

Meiosis: From a Single Diploid Cell to Four Unique Haploid Cells

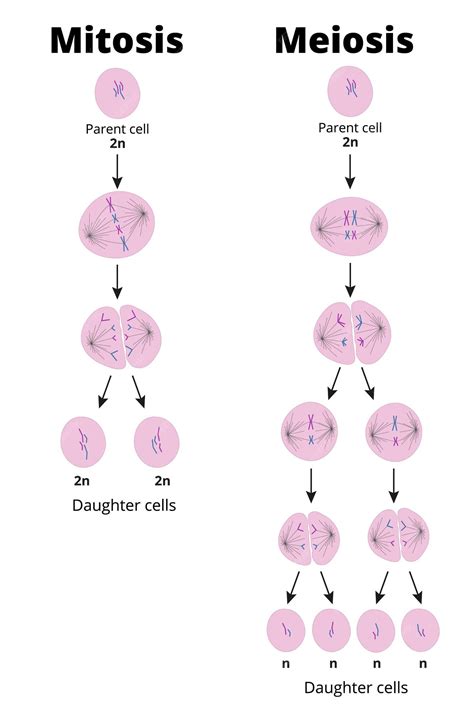

Meiosis is a fundamental process in sexually reproducing organisms, a specialized type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, resulting in the production of gametes – sperm and egg cells. This reduction is crucial for maintaining the constant chromosome number across generations. Let's delve into the intricacies of this fascinating process, starting with the initial diploid cell and tracing its transformation into four unique haploid cells.

Understanding the Starting Point: The Diploid Cell

Before embarking on the journey of meiosis, it's vital to understand the starting point: the diploid cell. A diploid cell (2n) contains two sets of chromosomes, one inherited from each parent. These chromosome sets are homologous, meaning they carry the same genes but may have different versions (alleles) of those genes. Think of it like having two copies of a recipe book – both books contain the same recipes, but the specific ingredients or instructions might slightly differ. This diploid cell is typically found in somatic cells (body cells) of an organism. The specific number of chromosomes varies across species; humans, for instance, have 46 chromosomes (2n=46), while fruit flies have 8 (2n=8).

The Significance of Homologous Chromosomes

The presence of homologous chromosomes is central to meiosis. These pairs of chromosomes ensure that each gamete receives one copy of each gene, maintaining genetic diversity. Furthermore, homologous chromosomes participate in a crucial event during meiosis I, called crossing over, which shuffles genetic material between them, leading to even greater genetic variation in the resulting gametes.

Meiosis I: Reductional Division

Meiosis is a two-stage process: Meiosis I and Meiosis II. Meiosis I is the reductional division, where the chromosome number is halved. This phase involves several key stages:

Prophase I: A Complex Stage of Pairing and Recombination

Prophase I is the longest and most complex stage of meiosis I. Several critical events occur during this phase:

-

Chromatin Condensation: The replicated chromosomes begin to condense, becoming visible under a microscope. Each chromosome consists of two sister chromatids joined at the centromere.

-

Synapsis and Tetrad Formation: Homologous chromosomes pair up, a process called synapsis. The paired homologous chromosomes, each composed of two sister chromatids, form a structure called a tetrad. This tetrad contains four chromatids in total.

-

Crossing Over: The most significant event of Prophase I is crossing over. Non-sister chromatids within a tetrad exchange segments of DNA at points called chiasmata. This process shuffles genetic information between homologous chromosomes, creating new combinations of alleles. Crossing over is a key source of genetic variation, contributing to the diversity of offspring.

-

Nuclear Envelope Breakdown: Towards the end of Prophase I, the nuclear envelope breaks down, releasing the chromosomes into the cytoplasm.

Metaphase I: Alignment of Homologous Pairs

In Metaphase I, the tetrads align at the metaphase plate, the equatorial plane of the cell. The orientation of each homologous pair at the metaphase plate is random, a phenomenon known as independent assortment. This random alignment is another major source of genetic variation, contributing to the uniqueness of each gamete.

Anaphase I: Separation of Homologous Chromosomes

During Anaphase I, homologous chromosomes separate and move towards opposite poles of the cell. Sister chromatids, however, remain attached at the centromere. This separation is a crucial step in reducing the chromosome number from diploid to haploid.

Telophase I and Cytokinesis: Formation of Two Haploid Cells

Telophase I sees the arrival of chromosomes at opposite poles. The nuclear envelope may reform, and the chromosomes may decondense. Cytokinesis, the division of the cytoplasm, follows, resulting in two haploid daughter cells. Each daughter cell now contains only one set of chromosomes, but each chromosome still consists of two sister chromatids.

Meiosis II: Equational Division

Meiosis II is similar to mitosis in that it separates sister chromatids, but it starts with haploid cells. This phase consists of:

Prophase II: Chromosome Condensation

Chromosomes condense again, and the nuclear envelope breaks down if it had reformed during Telophase I.

Metaphase II: Alignment of Sister Chromatids

Chromosomes align at the metaphase plate. This alignment is similar to that in mitosis, but now, only one set of chromosomes is present.

Anaphase II: Separation of Sister Chromatids

Sister chromatids separate and move towards opposite poles. This separation is crucial for generating four genetically distinct haploid cells.

Telophase II and Cytokinesis: Formation of Four Haploid Cells

Chromosomes arrive at opposite poles, and the nuclear envelope reforms. Cytokinesis then occurs, resulting in four haploid daughter cells. These cells are genetically unique due to crossing over and independent assortment.

The Outcome: Four Unique Haploid Cells

The culmination of meiosis is the production of four haploid (n) daughter cells from a single diploid (2n) cell. These haploid cells are genetically unique, differing from each other and from the original diploid parent cell. This genetic variation is a critical factor in evolution, providing the raw material for natural selection to act upon.

Genetic Variation: The Driving Force of Evolution

The mechanisms of crossing over and independent assortment during meiosis create enormous genetic diversity. This variation is essential for several reasons:

-

Adaptation: Genetic diversity allows populations to adapt to changing environments. Individuals with advantageous traits are more likely to survive and reproduce, passing on their beneficial genes to their offspring.

-

Resistance to Disease: Genetic variation enhances the ability of a population to resist diseases. A diverse gene pool makes it less likely that an entire population will be susceptible to a particular pathogen.

-

Evolutionary Novelty: Meiosis-driven genetic variation is the foundation for the generation of new species. As populations diverge genetically, they may eventually become reproductively isolated, leading to speciation.

Errors in Meiosis: Consequences and Significance

While meiosis is a remarkably precise process, errors can occur. These errors can lead to changes in chromosome number, such as aneuploidy, where cells have an abnormal number of chromosomes. Examples include Down syndrome (trisomy 21), where individuals have three copies of chromosome 21, and Turner syndrome, where females have only one X chromosome.

These errors highlight the critical role of meiosis in ensuring the accurate transmission of genetic information across generations. The consequences of meiotic errors can range from mild to severe, emphasizing the importance of proper chromosome segregation during this fundamental process.

Meiosis and Sexual Reproduction

The four haploid gametes produced by meiosis are essential for sexual reproduction. During fertilization, two gametes (typically one sperm and one egg) fuse, restoring the diploid chromosome number in the zygote, the fertilized egg. The zygote then undergoes mitosis to develop into a multicellular organism. The combination of genetic material from two parents, facilitated by meiosis and fertilization, contributes significantly to the genetic diversity within a species.

Conclusion

Meiosis, starting with a single diploid cell, is a meticulously orchestrated process that generates four unique haploid cells. This reduction in chromosome number, coupled with the mechanisms of crossing over and independent assortment, is crucial for maintaining genetic stability and driving the evolution of sexually reproducing organisms. The profound impact of meiosis on genetic diversity is evident in the incredible variety of life forms that inhabit our planet. The understanding of this process is fundamental to grasping the principles of heredity, genetics, and evolution. Further research continues to unravel the intricacies of meiosis, revealing more about its regulation and the significance of its role in shaping the biological world.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Lord Of The Flies Chapter 1 Summary

Mar 14, 2025

-

If You Suspect Information Has Been Improperly Or Unnecessarily Classified

Mar 14, 2025

-

Identify The Components Contained In Each Of The Following Lipids

Mar 14, 2025

-

Who Designates Whether Information Is Classified And Its Classification Level

Mar 14, 2025

-

Which Of The Following Is A True Statement

Mar 14, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Meiosis Starts With A Single Diploid Cell And Produces . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.