Receptors For Nonsteroid Hormones Are Located In _____.

Breaking News Today

Mar 15, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

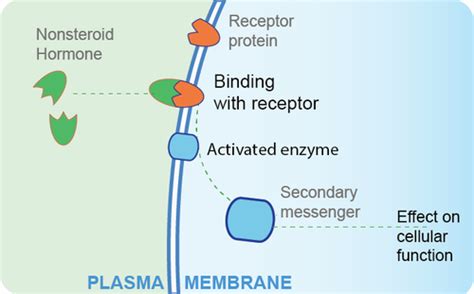

Receptors for Nonsteroid Hormones are Located in the Cell Membrane

Nonsteroid hormones, unlike their steroid counterparts, are unable to directly cross the plasma membrane of a target cell. This is due to their hydrophilic nature; they are water-soluble and cannot penetrate the hydrophobic lipid bilayer. Consequently, their receptors are strategically located on the surface of the cell, specifically within the cell membrane. This crucial location dictates the mechanism of action for these hormones, initiating a cascade of intracellular events that ultimately lead to the desired physiological response. Understanding the location of these receptors is fundamental to comprehending how nonsteroid hormones exert their influence on cellular function.

The Diverse Family of Cell Membrane Receptors

The cell membrane harbors a diverse array of receptors tailored to bind various nonsteroid hormones. These receptors belong to several distinct families, each employing a unique mechanism to transduce the hormonal signal into an intracellular response. The major classes include:

1. G Protein-Coupled Receptors (GPCRs)

This is by far the largest and most diverse family of cell surface receptors. GPCRs are characterized by their seven transmembrane α-helices. Upon hormone binding, a conformational change occurs, activating a heterotrimeric G protein associated with the cytoplasmic tail of the receptor. The activated G protein then initiates a signaling cascade, often involving second messengers such as cyclic AMP (cAMP), inositol triphosphate (IP3), and diacylglycerol (DAG).

Examples of hormones utilizing GPCRs:

- Adrenaline (epinephrine) and noradrenaline (norepinephrine): These hormones, crucial for the "fight or flight" response, bind to adrenergic receptors (α and β subtypes), triggering changes in heart rate, blood pressure, and metabolism.

- Glucagon: This hormone, involved in blood glucose regulation, binds to glucagon receptors, leading to glycogenolysis (breakdown of glycogen to glucose) in the liver.

- Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH): This hormone regulates thyroid hormone production by binding to TSH receptors on thyroid cells.

- Many peptide hormones: A vast number of peptide hormones, including those involved in digestion, growth, and reproduction, utilize GPCRs for signaling.

Mechanism of action: The binding of the hormone to the GPCR causes a conformational change, exchanging GDP for GTP on the α subunit of the G protein. This activated α subunit, along with βγ subunits, interacts with downstream effector molecules like adenylate cyclase (for cAMP production) or phospholipase C (for IP3 and DAG production). These second messengers then trigger a multitude of intracellular events, leading to the final physiological effect.

2. Receptor Tyrosine Kinases (RTKs)

RTKs are another significant class of cell membrane receptors. These receptors possess intrinsic enzymatic activity—tyrosine kinase—which phosphorylates tyrosine residues on intracellular proteins. Hormone binding to the extracellular domain of the RTK leads to receptor dimerization and subsequent autophosphorylation. These phosphorylated tyrosines serve as docking sites for other signaling molecules, triggering various downstream pathways, including the Ras/MAPK pathway and the PI3K/Akt pathway.

Examples of hormones utilizing RTKs:

- Insulin: This crucial hormone regulates glucose uptake, metabolism, and storage. It binds to insulin receptors, triggering a cascade that ultimately increases glucose transport into cells.

- Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1): Similar to insulin, IGF-1 plays a key role in growth and development.

- Epidermal growth factor (EGF): This hormone is involved in cell growth, proliferation, and differentiation.

Mechanism of Action: Hormone binding induces receptor dimerization, bringing the intracellular tyrosine kinase domains together. This facilitates autophosphorylation of tyrosine residues. These phosphotyrosines then recruit various signaling proteins, such as adaptor proteins (e.g., Grb2), which initiate downstream signaling cascades. These cascades can lead to changes in gene expression, cell growth, and metabolism.

3. Receptor Serine/Threonine Kinases

These receptors, similar to RTKs, possess intrinsic kinase activity, but they phosphorylate serine and threonine residues rather than tyrosine residues. These receptors are less common than GPCRs and RTKs but still play significant roles in various cellular processes.

Examples of hormones utilizing Receptor Serine/Threonine Kinases:

- Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β): This family of growth factors is involved in a wide range of cellular processes, including cell growth, differentiation, and apoptosis.

Mechanism of action: The binding of TGF-β to its receptor leads to receptor dimerization and activation of its serine/threonine kinase activity. This initiates downstream signaling cascades involving Smads, which regulate gene expression.

4. Ligand-Gated Ion Channels

These receptors are ion channels that open or close in response to hormone binding. This directly alters the membrane potential, influencing the excitability of the cell. These receptors are particularly important in the nervous system and other electrically excitable tissues.

Examples of hormones utilizing Ligand-Gated Ion Channels:

- Acetylcholine: This neurotransmitter binds to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, leading to the opening of ion channels and depolarization of the postsynaptic membrane.

- GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid): This neurotransmitter binds to GABA receptors, leading to the opening of chloride channels and hyperpolarization of the postsynaptic membrane.

Mechanism of action: The hormone directly binds to the receptor, inducing a conformational change that opens or closes the ion channel. This leads to a rapid change in membrane potential, affecting the cell's excitability.

Intracellular Signaling Cascades: Amplifying the Hormonal Signal

The location of nonsteroid hormone receptors in the cell membrane necessitates the utilization of intracellular signaling cascades to amplify the initial signal and ultimately elicit a substantial cellular response. The binding of a single hormone molecule to its receptor can trigger a series of events leading to the activation of numerous downstream effectors. This amplification is crucial because the number of hormone molecules is often relatively small compared to the magnitude of the cellular response.

For example, the activation of a single GPCR can lead to the activation of hundreds of G proteins, each of which can activate many effector enzymes, resulting in a significant amplification of the initial signal. This cascade effect ensures that even low concentrations of hormones can elicit a substantial physiological effect.

The Importance of Receptor Specificity and Affinity

The interaction between a hormone and its receptor is highly specific. Each hormone binds to a specific receptor with high affinity, ensuring that only the appropriate cells respond to a particular hormone. This specificity is critical for maintaining homeostasis and preventing unwanted side effects. Receptor affinity dictates the sensitivity of the cell to the hormone; higher affinity implies a greater response at lower hormone concentrations.

Diseases and Dysfunctions Related to Cell Membrane Receptors

Dysfunctions in cell membrane receptors for nonsteroid hormones can lead to a wide range of diseases and disorders. These dysfunctions can arise from genetic mutations affecting receptor structure or function, autoantibodies against receptors, or changes in receptor expression levels.

Examples include:

- Type 2 diabetes: Insulin resistance, a hallmark of type 2 diabetes, often involves defects in insulin receptor signaling.

- Hyperthyroidism: Autoantibodies against TSH receptors can lead to overproduction of thyroid hormones.

- Hypothyroidism: Defects in TSH receptors can result in insufficient thyroid hormone production.

Conclusion

The location of receptors for nonsteroid hormones within the cell membrane is a cornerstone of their mechanism of action. The diversity of membrane receptors, the amplification provided by intracellular signaling cascades, and the remarkable specificity of hormone-receptor interactions all contribute to the precise and effective regulation of numerous physiological processes. Understanding these intricate processes is crucial for comprehending health and disease, paving the way for the development of novel therapeutic strategies targeting these vital signaling pathways. Further research continues to unravel the complexities of these receptors and their roles in maintaining homeostasis and responding to various physiological demands. The field remains dynamic, with ongoing discoveries adding to our understanding of this crucial aspect of cellular communication.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Which Of The Following Statements Is Not A Hypothesis

Mar 15, 2025

-

Air Brake Equipped Trailers Made Before 1975

Mar 15, 2025

-

As A Non Confidential Employee Of A School District

Mar 15, 2025

-

Which Is A Physiological Description Rather Than An Anatomical One

Mar 15, 2025

-

Which Optical Media Has The Greatest Storage Capacity

Mar 15, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Receptors For Nonsteroid Hormones Are Located In _____. . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.