This Seals Up Gaps In A Piece Of Dna

Breaking News Today

Mar 21, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

This Seals Up Gaps in a Piece of DNA: Understanding DNA Repair Mechanisms

The intricate double helix of DNA, the blueprint of life, is surprisingly fragile. Constant exposure to internal and external factors like radiation, toxins, and even the normal metabolic processes within our cells can lead to damage in the form of DNA breaks, mutations, and other lesions. These disruptions can have profound consequences, potentially leading to cell death, disease, and even aging. Fortunately, cells possess a sophisticated arsenal of DNA repair mechanisms to maintain the integrity of their genome. This article delves deep into the fascinating world of DNA repair, specifically focusing on the mechanisms that seal up gaps in a piece of DNA.

The Perils of DNA Damage: Types of Breaks and Their Consequences

Before we explore the repair mechanisms, it’s crucial to understand the types of DNA damage that necessitate repair. A significant threat is the double-strand break (DSB), where both strands of the DNA helix are severed. DSBs are particularly dangerous because they can lead to chromosomal rearrangements, loss of genetic material, and cell death. Less severe, but still significant, are single-strand breaks (SSBs), where only one strand of the DNA is broken. While often less catastrophic than DSBs, SSBs can still lead to mutations if not repaired correctly. Other forms of DNA damage include base modifications (changes to individual nucleotide bases), bulky adducts (large molecules attached to DNA), and interstrand crosslinks (links between the two DNA strands).

Double-Strand Breaks: The Most Critical Damage

Double-strand breaks are arguably the most dangerous type of DNA damage. Their severity stems from the fact that they completely disrupt the DNA molecule, potentially leading to loss of genetic information or incorrect rejoining of the broken ends. This incorrect rejoining can result in chromosomal translocations, inversions, and deletions, all of which can contribute to genomic instability and cancer. The causes of DSBs are diverse and include:

- Ionizing radiation: X-rays and gamma rays can directly break the DNA backbone.

- Reactive oxygen species (ROS): These byproducts of cellular metabolism can damage DNA bases, leading to strand breakage.

- Topoisomerase inhibitors: These drugs, used in cancer chemotherapy, interfere with enzymes that manage DNA supercoiling and can induce DSBs.

- Replication fork collapse: Problems during DNA replication can lead to the collapse of the replication fork, resulting in DSBs.

Single-Strand Breaks: Less Severe, But Still Significant

Single-strand breaks are less severe than DSBs, as the unbroken strand can serve as a template for repair. However, if left unrepaired, SSBs can lead to mutations during DNA replication. The main causes of SSBs include:

- Exposure to certain chemicals: Some chemicals can directly damage DNA, leading to strand breakage.

- ROS: Similar to DSBs, reactive oxygen species can contribute to the formation of SSBs.

- Spontaneous hydrolysis: The spontaneous hydrolysis of the DNA backbone can also lead to SSBs.

DNA Repair Mechanisms: The Cellular Guardians

Cells have evolved a remarkable array of mechanisms to detect and repair various types of DNA damage. These mechanisms can be broadly classified into several categories, each with specific pathways and enzymes involved. The mechanisms that are most pertinent to sealing gaps in DNA are:

- Non-homologous end joining (NHEJ): This pathway directly joins the broken ends of a DSB without the need for a homologous template. It's a relatively fast and error-prone pathway.

- Homologous recombination (HR): This pathway utilizes a homologous DNA sequence (usually a sister chromatid) as a template to accurately repair the DSB. It's a slower but more accurate pathway.

- Base excision repair (BER): This pathway repairs small, non-helix-distorting base lesions. It's crucial in dealing with small lesions that could lead to more significant problems if left unattended.

- Nucleotide excision repair (NER): This pathway repairs bulky DNA lesions that distort the DNA helix, including those caused by UV radiation and certain chemicals.

Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): A Quick Fix

NHEJ is a crucial pathway for repairing DSBs, especially in the absence of a homologous template. This pathway is particularly active during the G1 phase of the cell cycle, before DNA replication. The process involves several steps:

- Recognition: The broken DNA ends are recognized by a complex of proteins, including Ku70/Ku80 heterodimer.

- End processing: The DNA ends may be processed to remove damaged nucleotides. This step is often less precise than in HR.

- Joining: The processed ends are joined by DNA ligase IV, completing the repair.

The accuracy of NHEJ is lower than HR, as it often involves the loss of a few nucleotides at the break site. This can lead to small insertions or deletions, potentially resulting in mutations. However, its speed and ability to function even without a homologous template make it a vital first responder to DSBs.

Homologous Recombination (HR): Precise Repair Using a Template

HR is a more accurate pathway for repairing DSBs, using a homologous DNA sequence (typically a sister chromatid) as a template to ensure fidelity. This pathway is mainly active during the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, after DNA replication. The process involves:

- Resection: The 5' ends of the broken DNA are resected, creating 3' single-stranded DNA overhangs.

- Strand invasion: One of the 3' overhangs invades the homologous DNA sequence, forming a D-loop.

- DNA synthesis: DNA polymerase uses the homologous sequence as a template to synthesize new DNA, filling in the gap in the broken strand.

- Resolution: The Holliday junctions are resolved, and the repaired DNA is ligated.

HR is significantly more accurate than NHEJ, as it utilizes a homologous sequence to guide the repair, minimizing the risk of errors. However, it's a slower process, requiring the availability of a homologous template.

Base Excision Repair (BER): Targeting Small Lesions

BER is a crucial pathway for repairing small, non-helix-distorting base lesions. These lesions can be caused by various factors, including oxidation, alkylation, and deamination. The process involves:

- Recognition and removal: DNA glycosylases recognize and remove the damaged base, creating an abasic site.

- Backbone cleavage: AP endonucleases cleave the DNA backbone at the abasic site.

- Gap filling: DNA polymerase fills in the gap, using the undamaged strand as a template.

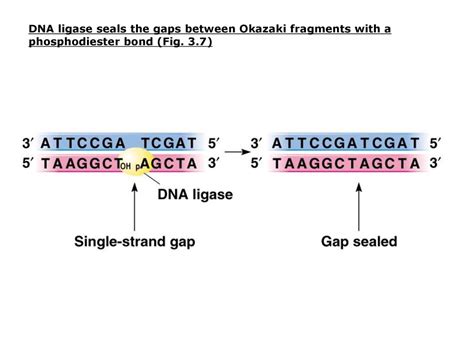

- Ligation: DNA ligase seals the nick.

BER is essential in maintaining genomic stability by preventing the accumulation of small lesions that could otherwise lead to larger, more damaging mutations.

Nucleotide Excision Repair (NER): Fixing Bulky Lesions

NER repairs bulky DNA lesions that distort the DNA helix. These lesions are often caused by UV radiation and certain chemicals. The process is more complex than BER and involves:

- Damage recognition: Specific proteins recognize the bulky lesion.

- DNA unwinding: Helicase unwinds the DNA around the lesion.

- Incision: Endonucleases make incisions on either side of the lesion.

- Excision: The damaged DNA segment is removed.

- Gap filling: DNA polymerase fills in the gap, using the undamaged strand as a template.

- Ligation: DNA ligase seals the nick.

The Interplay of DNA Repair Pathways

The various DNA repair pathways are not isolated entities but rather work in concert to maintain genomic integrity. The choice of which pathway to employ depends on several factors, including the type of DNA damage, the cell cycle phase, and the availability of repair factors. For instance, DSB repair often involves a choice between NHEJ and HR, with HR being preferred when a homologous template is available. Minor lesions are typically handled efficiently by BER or NER. The intricate interplay and redundancy of these mechanisms highlight their importance in protecting the genome.

Clinical Significance: Defects and Diseases

Defects in DNA repair pathways are implicated in a wide range of human diseases, most notably cancer. Individuals with inherited mutations in genes involved in DNA repair are at a significantly increased risk of developing various cancers. These hereditary defects highlight the critical role of efficient DNA repair in preventing genomic instability and tumorigenesis. Furthermore, understanding DNA repair mechanisms is crucial for developing novel cancer therapies. Targeting DNA repair pathways can enhance the efficacy of existing cancer treatments and create new therapeutic strategies.

Conclusion: The Essential Role of DNA Repair

The ability of cells to seal gaps in DNA is an essential aspect of maintaining genomic integrity and ensuring the faithful transmission of genetic information. The diverse and sophisticated mechanisms involved, from the swift action of NHEJ to the precision of HR, underscore the cell’s commitment to preserving its genetic blueprint. Defects in these repair pathways can have devastating consequences, leading to a wide range of diseases, particularly cancer. Continued research into the intricacies of DNA repair will undoubtedly lead to a better understanding of disease mechanisms and the development of innovative therapeutic strategies. The ongoing exploration of these fascinating mechanisms reveals the remarkable resilience and adaptability of life itself.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

What Is The Difference Between Accurate Data And Reproducible Data

Mar 21, 2025

-

Which Story Element Most Closely Belongs To Gothic Literature

Mar 21, 2025

-

Pedro Y Natalia No Nos Dan Las Gracias

Mar 21, 2025

-

In The Early 1900s The Chicago Defender Was

Mar 21, 2025

-

Which Of The Following Best Describes A Black Hole

Mar 21, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about This Seals Up Gaps In A Piece Of Dna . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.