Which Experiment Involves The Use Of Classical Conditioning

Breaking News Today

Mar 14, 2025 · 8 min read

Table of Contents

Which Experiments Involve the Use of Classical Conditioning? A Deep Dive into Pavlovian Principles

Classical conditioning, also known as Pavlovian conditioning, is a fundamental learning process where an association is made between a neutral stimulus and a naturally occurring stimulus. This association leads to the neutral stimulus eliciting a response similar to that of the naturally occurring stimulus. Understanding classical conditioning is crucial in various fields, from psychology and animal training to marketing and advertising. This article explores several key experiments that beautifully illustrate the principles of classical conditioning, delving deep into their methodologies, results, and lasting impact on our understanding of learning.

The Original: Pavlov's Dogs and the Salivary Response

Arguably the most famous experiment in classical conditioning is Ivan Pavlov's work with dogs. Pavlov, a Russian physiologist, was initially studying digestion when he observed a fascinating phenomenon: his dogs began salivating not only at the sight of food (an unconditioned stimulus, UCS, triggering an unconditioned response, UCR), but also at the sight of the lab assistants who usually brought the food. This observation sparked his groundbreaking research into learned associations.

Methodology:

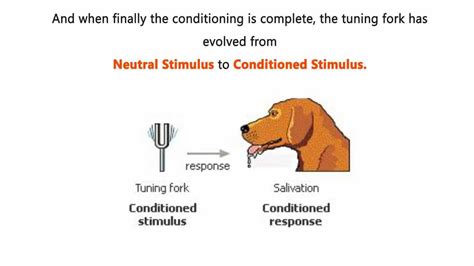

Pavlov's experiment systematically paired a neutral stimulus (a bell) with the unconditioned stimulus (food). Initially, the bell (conditioned stimulus, CS) elicited no salivary response. However, through repeated pairings of the bell and food, the dogs eventually began to salivate (conditioned response, CR) at the sound of the bell alone, even without the presence of food.

Results and Significance:

The results demonstrated the acquisition of a conditioned response through the association of a neutral stimulus with an unconditioned stimulus. This groundbreaking work laid the foundation for understanding classical conditioning and its implications for learning and behavior. Pavlov's experiment highlighted the power of association and how seemingly simple pairings can lead to significant behavioral changes. His rigorous methodology and quantifiable results solidified classical conditioning as a valid and impactful area of psychological research. The terminology he introduced—UCS, UCR, CS, and CR—remains standard in the field today.

Little Albert: A Case Study in Fear Conditioning

John B. Watson and Rosalie Rayner's infamous "Little Albert" experiment dramatically illustrated the application of classical conditioning to the development of fear. This study, while ethically problematic by today's standards, provided significant insights into the learning of phobias.

Methodology:

Nine-month-old Albert was presented with various stimuli, including a white rat, a rabbit, a dog, and masks. Initially, Albert showed no fear. However, Watson and Rayner paired the presentation of the white rat (CS) with a loud, startling noise (UCS) that naturally elicited fear (UCR) in Albert. After several pairings, Albert began to show fear (CR) of the white rat alone, even without the loud noise. Furthermore, the fear response generalized to other similar stimuli, such as a rabbit and a fur coat.

Results and Significance:

The experiment demonstrated that fear responses can be learned through classical conditioning. The generalization of the fear response showed the ability of conditioned responses to extend beyond the original stimulus. This study highlighted the potential for classical conditioning to play a significant role in the development of phobias and anxieties, although the ethical concerns surrounding the experiment have led to its critical re-evaluation and a decrease in similar studies. The lack of counterconditioning to eliminate Albert's fear remains a point of significant ethical critique.

The Eye-Blink Response: Precision and Control

While Pavlov's dogs and Little Albert provided dramatic demonstrations, studies focusing on the eye-blink response offer a more precise and controlled examination of classical conditioning. These experiments often involve the use of rabbits or other animals, offering a greater level of experimental manipulation and control.

Methodology:

Researchers typically pair a neutral stimulus (such as a tone or light) with an unconditioned stimulus (such as a puff of air to the eye), which elicits an unconditioned eye-blink response. Through repeated pairings, the neutral stimulus becomes a conditioned stimulus, eliciting a conditioned eye-blink response. These experiments allow for meticulous measurement of the timing and strength of the conditioned response.

Results and Significance:

The consistent and measurable nature of the eye-blink response makes it an ideal model for studying the mechanisms of classical conditioning. These experiments have provided valuable insights into the neural pathways involved in learning and memory. The ability to precisely control and measure the conditioned response allows researchers to investigate factors influencing the strength and duration of conditioning, such as the timing of stimulus presentation and the number of pairings.

Taste Aversion Learning: A Unique Application

Taste aversion learning presents a unique twist on classical conditioning. It demonstrates that a single pairing of a neutral stimulus (a specific food) with an unconditioned stimulus (nausea or illness) can lead to a strong conditioned aversion to that food.

Methodology:

Animals are typically given a novel food (CS) and then, after a short delay, are administered a drug or treatment that induces nausea (UCS), resulting in illness (UCR). Even with a single pairing, the animal subsequently avoids the novel food (CR), demonstrating a strong conditioned aversion.

Results and Significance:

Taste aversion learning defies some of the principles of traditional classical conditioning, particularly concerning the timing of stimulus pairings. The long delay between the conditioned stimulus (food) and the unconditioned stimulus (nausea) still leads to conditioning, suggesting a biological preparedness for associating taste with illness. This has implications for understanding survival mechanisms and the evolutionary basis of learning. This phenomenon is particularly relevant in the context of chemotherapy, where patients often develop aversions to foods consumed before treatment.

Conditioned Emotional Responses: Beyond Salivation

Classical conditioning isn't limited to simple physiological responses like salivation or eye-blinking. It also plays a crucial role in shaping our emotional responses. Experiments exploring conditioned emotional responses demonstrate how neutral stimuli can become associated with emotional states.

Methodology:

These experiments often involve pairing a neutral stimulus (e.g., a specific image or music) with an unconditioned stimulus that elicits a strong emotional response (e.g., a shocking image or loud noise). Repeated pairings can lead the neutral stimulus to evoke a similar emotional response.

Results and Significance:

The development of conditioned emotional responses helps explain how we develop preferences, aversions, and even phobias associated with various stimuli. This has implications for understanding the formation of attitudes, prejudices, and emotional responses to advertising and marketing materials. The power of associating a product or brand with positive emotions demonstrates the practical applications of classical conditioning in shaping consumer behavior.

Extinction and Spontaneous Recovery: The Dynamics of Conditioning

Understanding classical conditioning isn't just about acquisition; it's also about the processes of extinction and spontaneous recovery. Experiments examining these phenomena illustrate the dynamic nature of learned associations.

Methodology:

After a conditioned response is established, the conditioned stimulus is presented repeatedly without the unconditioned stimulus. This process of extinction leads to a gradual weakening and eventual disappearance of the conditioned response. However, after a period of rest, presenting the conditioned stimulus may elicit a weak conditioned response again, demonstrating spontaneous recovery.

Results and Significance:

Extinction doesn't erase the learned association; it merely inhibits it. Spontaneous recovery shows the enduring nature of learned associations, even after they appear to be extinguished. This highlights the complexity of learning and the interplay between acquisition, extinction, and recovery. Understanding these processes is crucial in therapeutic interventions such as exposure therapy for phobias, where extinction plays a key role.

Higher-Order Conditioning: Building Upon Associations

Higher-order conditioning extends the principles of classical conditioning by demonstrating how a conditioned stimulus can itself become a basis for further conditioning.

Methodology:

Once a conditioned response is established (e.g., a bell eliciting salivation in Pavlov's dogs), a new neutral stimulus is paired with the conditioned stimulus (bell). This new stimulus, through association with the already conditioned stimulus, can eventually elicit the conditioned response without the original unconditioned stimulus.

Results and Significance:

Higher-order conditioning showcases the ability of learned associations to build upon each other, creating complex chains of stimuli and responses. This has implications for understanding the development of intricate behavioral patterns and the generalization of learned responses to a wider range of stimuli. It exemplifies the cumulative nature of learning and the intricate web of associations that shape our behavior.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of Classical Conditioning

The experiments discussed above represent a small sample of the extensive research conducted on classical conditioning. From Pavlov's pioneering work to contemporary investigations, these studies have fundamentally shaped our understanding of learning, behavior, and the complexities of the human (and animal) mind. The enduring legacy of classical conditioning lies in its ability to explain a wide array of phenomena, from the acquisition of simple reflexes to the development of complex emotional responses and phobias. Understanding the principles of classical conditioning remains essential across diverse fields, from psychology and education to marketing and therapy, offering valuable insights into the mechanisms of learning and the shaping of behavior. The continued exploration of this fundamental learning process promises to yield further insights into the intricacies of the human experience.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

The Ideas Addressed In The Image Most Directly Relate To

Mar 15, 2025

-

Jasmin Belongs To The Chess Club On Her Campus

Mar 15, 2025

-

Select The Category That Would Yield Quantitative Data

Mar 15, 2025

-

Nominal Gross Domestic Product Measures The Dollar Value Of

Mar 15, 2025

-

What Does A Drowning Swimmer Commonly Look Like

Mar 15, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Which Experiment Involves The Use Of Classical Conditioning . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.