According To Hume Section 2 Some Examples Of Ideas Include

Breaking News Today

Mar 26, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

According to Hume, Section 2: A Deep Dive into Examples of Ideas

David Hume's A Treatise of Human Nature, specifically Section 2 of Book I, "Of the Ideas of the Memory and Imagination," lays the groundwork for his empiricist philosophy. This section is crucial because it details how our minds process and arrange impressions to form complex ideas. While Hume doesn't explicitly list "examples of ideas" in a numbered fashion, his discussion provides ample material to unpack and understand the various ways ideas are generated and function. This article will delve into Hume's framework, extracting several key examples of ideas, analyzing their origins, and demonstrating how they relate to his broader philosophical project.

Understanding Hume's Empiricism: Impressions and Ideas

Before exploring specific examples, it's crucial to grasp Hume's fundamental distinction between impressions and ideas. Impressions are the immediate sensory experiences that are lively and forceful – the direct impact of sensations, passions, and emotions. These are the raw materials of our mental life. Ideas, on the other hand, are the faint copies of impressions. They are weaker, less vivid representations that are recalled or imagined.

Hume's contention is that all our ideas are ultimately derived from impressions. This is his famous "copy principle." No idea can exist without a corresponding impression; the mind is not capable of generating completely novel ideas from nothing. This principle forms the cornerstone of his empiricism, arguing against innate ideas or concepts that are not derived from experience.

Examples of Ideas According to Hume's Framework

Let's now examine several examples of ideas, categorizing them based on how they are formed and their relation to impressions:

1. Simple Ideas: These are the most basic and direct copies of impressions. They are not complex; they are the direct reflections of single sensory experiences.

- Example: The idea of redness. This idea is derived from the impression of seeing something red. You have the immediate sensory experience (impression) of redness, and this leaves a weaker, less vivid copy (idea) in your mind. You can later recall the idea of redness without the presence of the red object. Similarly, the ideas of sweetness, coldness, or loudness directly correspond to their respective impressions.

- Example: The idea of pain. The intense feeling of pain (impression) leaves behind a weaker memory or idea of that pain, which can be recalled later. This idea might trigger an associated emotion (fear, anxiety) but its foundational element remains the copy of the initial sensory experience.

- Significance: Simple ideas, according to Hume, illustrate the copy principle most directly. They demonstrate how our minds passively receive sensory input and translate it into mental representations.

2. Complex Ideas: These are formed by combining, compounding, or relating simple ideas. Hume argues that the mind actively assembles these simpler elements into more complex and elaborate concepts.

- Example: The idea of an apple. This isn't a single simple impression; it is a combination of several simple ideas: the idea of redness (or greenness), the idea of roundness, the idea of smoothness, the idea of a certain weight, and perhaps even the idea of a particular smell or taste. These individual simple ideas, all derived from impressions, are combined to form the complex idea of an "apple."

- Example: The idea of a unicorn. Although unicorns don't exist in reality (as far as we know!), the idea is still formed by combining simple ideas that are derived from impressions. The idea of a horn, the idea of horse-like legs, and the idea of a white coat, are all components derived from real-world impressions, even though the combination itself is fictional. This showcases the mind's ability to create new ideas by rearranging existing ones.

- Significance: Complex ideas highlight the mind's active role in organizing sensory information. They demonstrate the mind's capacity for creativity, albeit constrained by the limitations of the impressions available.

3. Abstract Ideas: These ideas represent general concepts, rather than specific instances. They require a further level of mental processing beyond simply combining simple ideas.

- Example: The idea of justice. This isn't a single sensory impression. Instead, it's an abstraction derived from observing various instances of actions perceived as just or unjust. The mind extracts common features from these different experiences to form a general concept of justice. This process involves comparison, abstraction, and the creation of a generalized representation.

- Example: The idea of beauty. Like justice, beauty is subjective. It's not a direct sensory input but rather a complex idea formed by comparing and contrasting various experiences perceived as beautiful. Different individuals will have different sets of impressions that inform their idea of beauty, reflecting the subjectivity of this abstract concept.

- Significance: Abstract ideas present a challenge to the copy principle. While not directly copied from a single impression, Hume argues they are ultimately derived from impressions, as they are formed through a mental process of comparing and contrasting multiple instances.

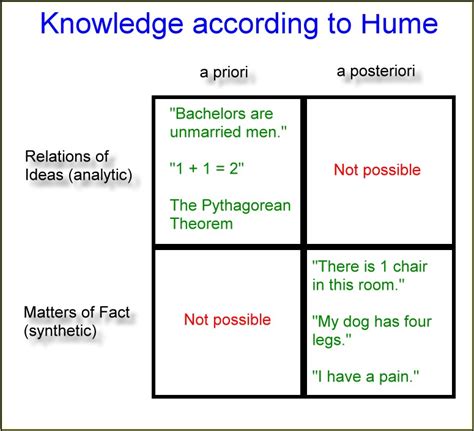

4. Relations of Ideas: These are not ideas derived directly from impressions but rather ideas that are known through reason alone. They are necessary truths that are true by definition and independent of experience.

- Example: The idea that all bachelors are unmarried. This isn't derived from observation of bachelors. It's a logical truth that is self-evident based on the definition of "bachelor."

- Example: Mathematical relationships like 2 + 2 = 4. These aren't derived from sensory experience; they are true by the definitions of the terms involved.

- Significance: Relations of ideas show a category of knowledge that differs from those based on impressions. They demonstrate the mind's capacity for rational thought and its ability to generate truths independently of empirical observation. Although even the terms used in mathematical relationships originate from experience.

5. Fictional Ideas: This category shows Hume's allowance for the creative power of the mind, even in the absence of corresponding impressions.

- Example: The idea of a centaur is a fictional idea, combining ideas of a horse and a human, each derived from impressions but the combined idea has no real-world counterpart.

- Example: The idea of a fairy. Like the centaur, it is a composite of impressions (perhaps smallness, wing-like structures, magical qualities), which combine to create an idea that doesn't have a physical basis.

- Significance: While fictional, they highlight that even ideas without a direct counterpart in reality still adhere to Hume's general framework, as they are constructed using the mind's capacity to rearrange and recombine impressions.

The Significance of Hume's Analysis of Ideas

Hume's analysis of ideas, particularly in Section 2, is crucial to understanding his broader philosophical project. By demonstrating how all ideas are ultimately derived from impressions, he provides a powerful argument against rationalism and innate ideas. His framework emphasizes the importance of experience in shaping our knowledge and understanding of the world. The distinctions between simple and complex ideas, abstract ideas, and relations of ideas help us classify and understand the different types of knowledge we possess. Further, the inclusion of fictional ideas shows the creative capacity of the mind even within the limits of experience.

This thorough examination of Hume's framework helps to understand the intricacies of his empiricism. It underscores the importance of sensory experiences as the foundation of all our knowledge and ideas. By acknowledging the complexities of constructing ideas, Hume offers a detailed map of how the mind functions, highlighting the interplay between passive reception of impressions and active construction and arrangement of ideas. This analysis remains highly relevant in contemporary philosophy, providing a foundation for many subsequent discussions on knowledge, perception, and the nature of the mind.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Middle Adulthood Is Referred To As The Sandwich Generation Because

Mar 29, 2025

-

Which Of The Following Statements About Human Rights Is True

Mar 29, 2025

-

What Is The Positive Phase Of Drinking

Mar 29, 2025

-

An Example Of Sustainable Material Use Would Be

Mar 29, 2025

-

Porters Five Competitive Forces Form A Model For Analysis

Mar 29, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about According To Hume Section 2 Some Examples Of Ideas Include . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.