If A Market Is Not In Equilibrium

Breaking News Today

Apr 02, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

When Markets Aren't in Equilibrium: Understanding Disequilibrium Dynamics

Markets, in their ideal form, strive for equilibrium – a state where supply and demand are balanced, and prices stabilize. However, the reality is far more complex. Markets are dynamic entities, constantly fluctuating due to a multitude of internal and external factors. Understanding what happens when a market is not in equilibrium is crucial for investors, businesses, and policymakers alike. This article delves deep into the dynamics of market disequilibrium, exploring its causes, consequences, and the mechanisms that either exacerbate or alleviate it.

Understanding Market Equilibrium: A Baseline

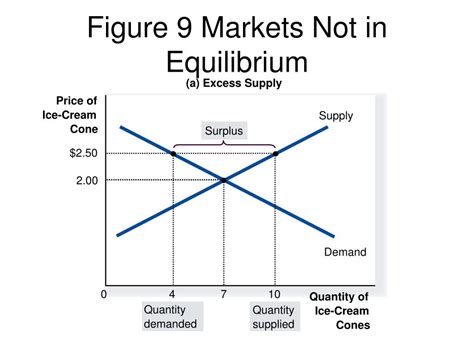

Before we explore disequilibrium, let's briefly revisit the concept of market equilibrium. Equilibrium is reached when the quantity demanded by consumers equals the quantity supplied by producers at a specific price point. This price is known as the equilibrium price, and the corresponding quantity is the equilibrium quantity. At this point, there's no pressure for the price or quantity to change, assuming all other factors remain constant. This is a theoretical ideal, a benchmark against which real-world market behavior can be measured.

Causes of Market Disequilibrium

Markets deviate from equilibrium due to a variety of factors, both predictable and unpredictable. These can be broadly categorized as:

1. Shifts in Demand:

- Changes in Consumer Preferences: Trends, fads, and evolving tastes can significantly alter demand. A sudden surge in popularity for a particular product will create a shortage (excess demand) at the existing price, pushing the price upwards until a new equilibrium is reached. Conversely, a decline in popularity will lead to a surplus (excess supply), forcing prices down.

- Changes in Consumer Income: An increase in disposable income generally leads to higher demand for normal goods, creating a shortage and driving prices up. Conversely, a decrease in income might reduce demand, leading to a surplus and lower prices.

- Changes in Prices of Related Goods: The price of substitute goods (goods that can be used in place of each other) and complementary goods (goods that are consumed together) can significantly impact demand. For instance, a price increase in a substitute good might boost demand for the original good, causing a shortage. A price increase in a complementary good might reduce the demand for the original good, leading to a surplus.

- Changes in Consumer Expectations: Anticipated future price changes, economic conditions, or product availability can influence current demand. For example, anticipation of a price increase might lead to increased current demand, creating a temporary shortage.

- Changes in Population: A growth in population, especially in a specific demographic, directly impacts the overall demand for certain goods and services.

2. Shifts in Supply:

- Changes in Input Costs: Increases in the cost of raw materials, labor, or energy can reduce the profitability of production, leading to a decrease in supply and a potential shortage. Conversely, decreases in input costs can increase supply, potentially leading to a surplus.

- Technological Advancements: Technological breakthroughs can boost productivity, leading to an increase in supply at various price points. This can lead to lower prices and increased consumption, eventually establishing a new equilibrium.

- Government Policies: Taxes, subsidies, regulations, and trade policies significantly impact supply. Taxes increase production costs, reducing supply, while subsidies can increase supply. Regulations can constrain supply, while trade policies (tariffs, quotas) affect the availability of imported goods.

- Natural Events and Disasters: Unexpected events like natural disasters, pandemics, or severe weather can disrupt supply chains, leading to significant shortages and price spikes.

- Producer Expectations: Similar to consumer expectations, producer expectations about future prices or market conditions can influence their current supply decisions.

3. Government Intervention:

Governments often intervene in markets through price controls, taxes, and subsidies. These interventions can deliberately create disequilibrium. For example:

- Price Ceilings: Setting a maximum price below the equilibrium price creates a shortage, as demand exceeds supply at the artificially low price.

- Price Floors: Setting a minimum price above the equilibrium price creates a surplus, as supply exceeds demand at the artificially high price.

- Taxes: Taxes on goods increase their price, reducing demand and supply. The new equilibrium point will reflect the impact of the tax.

- Subsidies: Subsidies reduce the cost of production, increasing supply. The new equilibrium point will reflect the impact of the subsidy.

Consequences of Market Disequilibrium

Disequilibrium situations have significant consequences for various stakeholders:

- Shortages: Lead to higher prices, rationing, black markets, and potential social unrest if essential goods are affected. Consumers face difficulties obtaining goods, potentially leading to dissatisfaction and reduced economic activity.

- Surpluses: Result in lower prices, potential waste of resources (unsold goods), and financial losses for producers. Producers might be forced to reduce production or exit the market, leading to job losses and decreased economic activity in the specific sector.

- Price Volatility: Disequilibrium often leads to volatile price fluctuations, creating uncertainty for both producers and consumers. This volatility can make it difficult to plan for the future and can deter investment.

- Inefficient Resource Allocation: Disequilibrium signifies that resources are not being allocated optimally. In a shortage, consumers willing to pay higher prices are not fully satisfied, while in a surplus, resources are wasted on producing goods that are not in sufficient demand.

- Reduced Economic Welfare: Disequilibrium generally reduces overall economic welfare, as consumers and producers do not achieve the maximum possible benefits from market transactions.

Mechanisms to Restore Equilibrium

Markets have inherent mechanisms that tend to restore equilibrium over time, although the speed and effectiveness of these mechanisms vary:

- Price Adjustment: The most fundamental mechanism. In a shortage, prices tend to rise, reducing demand and increasing supply until equilibrium is reached. Conversely, in a surplus, prices fall, increasing demand and decreasing supply until equilibrium is restored.

- Market Signals: Prices act as signals to both producers and consumers. High prices signal to producers to increase production and to consumers to reduce consumption, while low prices signal the opposite.

- Innovation and Technological Change: Technological advancements can shift supply curves, leading to new equilibrium points with potentially lower prices and increased efficiency.

- Government Intervention (Corrective Measures): While government intervention can create disequilibrium, it can also help restore it by addressing underlying supply and demand imbalances. For example, removing price controls or implementing targeted subsidies can facilitate a return to equilibrium.

- Speculation and Futures Markets: Speculative trading in futures markets can help anticipate future supply and demand conditions, potentially mitigating the severity of disequilibrium events.

Examples of Market Disequilibrium

Numerous real-world examples illustrate the dynamics of market disequilibrium:

- Oil Price Shocks: Geopolitical events or supply chain disruptions can drastically reduce the supply of oil, leading to significant price increases and shortages.

- Housing Market Bubbles: Periods of rapid price increases in the housing market, often fueled by speculation, eventually lead to unsustainable levels of demand, followed by a crash and a surplus of housing.

- Agricultural Commodity Markets: Weather events like droughts or floods can significantly impact agricultural yields, leading to shortages and higher prices for staple foods.

- Pandemics and Supply Chain Disruptions: The COVID-19 pandemic exemplified how unexpected events can dramatically disrupt supply chains, leading to temporary shortages of essential goods like medical supplies and personal protective equipment.

Conclusion: Navigating the Complexities of Disequilibrium

Market disequilibrium is an inherent characteristic of dynamic economic systems. Understanding its causes, consequences, and the mechanisms that restore equilibrium is essential for informed decision-making in various contexts. While the ideal of perfect equilibrium remains a theoretical construct, grasping the forces that drive market deviations provides valuable insights for businesses, investors, and policymakers seeking to navigate the complexities of the real world. The ability to anticipate and respond effectively to disequilibrium situations can significantly improve the efficiency and stability of markets, fostering economic growth and welfare. By analyzing the interplay of supply and demand, understanding the influence of external factors, and appreciating the inherent resilience of market mechanisms, we can better manage the challenges and harness the opportunities presented by a world of constantly shifting economic forces.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

The Most Popular Linux Platform For Mobile Phones Is

Apr 03, 2025

-

Mosses Are Located In Which Zone Of Deciduous Forests

Apr 03, 2025

-

How Does Co2 Level Affect Oxygen Production

Apr 03, 2025

-

Ohio Cosmetology State Board Exam Practice Test

Apr 03, 2025

-

Which Type Of Address Is The Ip Address 198 162 12 254 24

Apr 03, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about If A Market Is Not In Equilibrium . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.