What Are The Qualities Of A Good Hypothesis

Breaking News Today

Apr 01, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

What are the Qualities of a Good Hypothesis?

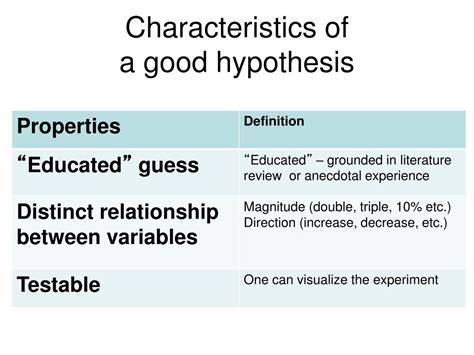

A hypothesis is a testable statement that proposes a possible explanation for an observation or phenomenon. It’s the crucial bridge between initial observation and scientific investigation, guiding the research process and shaping the way data is collected and analyzed. A good hypothesis, however, isn't just any guess; it possesses specific qualities that enhance its value and potential for contributing to knowledge. This article delves into the essential characteristics of a strong hypothesis, providing examples and guidance for crafting hypotheses that are both scientifically sound and practically useful.

The Cornerstones of a Good Hypothesis: Testability and Falsifiability

The most fundamental qualities of a good hypothesis are its testability and falsifiability. These two concepts are intrinsically linked and form the bedrock of scientific inquiry.

Testability: The Ability to be Empirically Investigated

A testable hypothesis can be subjected to empirical investigation. This means that it's possible to design experiments or studies that collect data to either support or refute the hypothesis. The methodology for testing must be clearly defined, outlining the variables to be measured, the methods of data collection, and the statistical analyses to be performed. If a hypothesis cannot be tested, it's essentially meaningless from a scientific perspective.

Example of a Testable Hypothesis: "Increased exposure to sunlight correlates with higher levels of Vitamin D in the blood." This hypothesis can be tested by measuring sunlight exposure and blood Vitamin D levels in a sample population.

Example of an Untestable Hypothesis: "The universe is governed by a sentient, invisible force." While intriguing, this hypothesis is difficult to test due to the nature of the "sentient, invisible force" – there are no measurable parameters or defined methods to investigate its influence.

Falsifiability: The Possibility of Being Proven Wrong

A falsifiable hypothesis can be proven wrong. This doesn't mean it's likely to be wrong, but rather that it's possible to conceive of observations or experimental results that would contradict the hypothesis. A hypothesis that is incapable of being disproven is often considered pseudoscience, as it lacks the critical element of empirical refutation. Falsifiability is crucial for the advancement of scientific knowledge, as it encourages rigorous testing and the refinement of theories.

Example of a Falsifiable Hypothesis: "Plants grown in nutrient-rich soil will exhibit faster growth rates than plants grown in nutrient-poor soil." This could be proven wrong if the experiment showed no significant difference in growth rates between the two groups.

Example of an Unfalsifiable Hypothesis: "All events are predetermined." This hypothesis, while philosophically interesting, is practically unfalsifiable because any observation could be interpreted as consistent with pre-determination. There's no conceivable experiment or observation that could definitively prove it false.

Beyond Testability and Falsifiability: Other Crucial Qualities

While testability and falsifiability are paramount, other qualities further enhance the strength and usefulness of a hypothesis:

Clarity and Specificity: Precise Language and Defined Variables

A good hypothesis is clearly and concisely stated, using precise language to avoid ambiguity. The variables involved should be explicitly defined, leaving no room for misinterpretation. Vague or overly broad hypotheses are difficult to test and often yield inconclusive results.

Example of a Clear Hypothesis: "Individuals who consume a diet high in saturated fat will have significantly higher levels of LDL cholesterol compared to individuals who consume a diet low in saturated fat." This specifies the variables (diet, saturated fat, LDL cholesterol) and the expected relationship between them.

Example of an Unclear Hypothesis: "Eating healthy foods is good for you." This is far too vague. What constitutes "healthy foods"? What are the specific benefits? The hypothesis lacks the precision needed for empirical investigation.

Relevance and Significance: Addressing a Meaningful Question

A strong hypothesis addresses a relevant and significant research question. It should contribute to existing knowledge, filling a gap in understanding or offering a novel perspective on a known problem. A hypothesis that investigates trivial matters or replicates already established findings is less valuable.

Example of a Relevant Hypothesis: "Exposure to violent video games is associated with increased aggression in adolescents." This addresses a contemporary societal concern and potentially informs public health policies.

Example of a Less Relevant Hypothesis: "The average height of students in a specific classroom is 5'6"." While testable, this hypothesis lacks broader significance unless it is part of a larger study on growth patterns.

Plausibility and Consistency: Alignment with Existing Knowledge

Although a hypothesis should be novel and potentially groundbreaking, it should also be plausible and consistent with existing scientific knowledge. While it’s permissible to challenge established theories, a hypothesis that completely contradicts well-established facts requires substantial justification and evidence.

Example of a Plausible Hypothesis: "Regular exercise improves cardiovascular health." This aligns with a wealth of existing research on the benefits of exercise.

Example of a Less Plausible Hypothesis: "Human beings can fly without the aid of any technology." This directly contradicts established laws of physics and requires extraordinary evidence to support it.

Simplicity and Parsimony: Ockham's Razor in Action

When faced with multiple hypotheses explaining the same phenomenon, the simplest hypothesis – the one requiring the fewest assumptions – is generally preferred. This principle, known as Occam's Razor, emphasizes that unnecessary complexity should be avoided. A simpler hypothesis is often easier to test and interpret.

Example: Let's say two hypotheses explain a decline in bird populations: 1) A new parasite is impacting the birds, and 2) A combination of climate change, habitat loss, and a new parasite are impacting the birds. While both are plausible, the first (simpler) hypothesis would be tested first.

The Iterative Nature of Hypothesis Development

Developing a robust hypothesis is often an iterative process. It rarely emerges fully formed on the first attempt. Researchers typically refine their hypotheses based on initial findings, literature reviews, and discussions with colleagues. This ongoing refinement ensures that the research question remains focused and the investigation remains relevant.

The process frequently involves:

- Observing and Questioning: Identifying a phenomenon that requires explanation.

- Background Research: Reviewing existing literature to determine what is already known and to identify potential gaps in understanding.

- Formulating a Preliminary Hypothesis: Developing an initial testable statement.

- Testing and Refining: Conducting experiments or studies to test the hypothesis and modifying it based on the results.

- Iterating and Revising: Repeating the testing and refinement process until a robust and well-supported hypothesis is obtained.

Examples of Strong Hypotheses Across Disciplines

To further illustrate the qualities of a good hypothesis, let's examine examples from different scientific fields:

Psychology: "Individuals with high levels of social anxiety will exhibit greater avoidance behavior in social situations than individuals with low levels of social anxiety." (Clearly defined variables, testable through observation and questionnaires, falsifiable if no significant difference is found).

Biology: "Plants exposed to higher concentrations of carbon dioxide will show increased rates of photosynthesis." (Testable through controlled experiments, falsifiable if no increase or even a decrease in photosynthesis is observed).

Economics: "Increased government spending on infrastructure projects will lead to a significant increase in job creation in the construction sector." (Testable through econometric analysis, falsifiable if job creation remains stagnant or decreases).

Physics: "The speed of light in a vacuum is a universal constant." (This fundamental principle has been extensively tested and repeatedly confirmed, although future findings could potentially challenge this).

Conclusion: The Foundation of Scientific Discovery

A strong hypothesis is the cornerstone of any successful scientific investigation. By understanding and applying the principles of testability, falsifiability, clarity, relevance, plausibility, and parsimony, researchers can formulate hypotheses that are both insightful and effective in advancing our knowledge. Remember that hypothesis development is a dynamic process, requiring iterative refinement and a willingness to adapt as new evidence emerges. The pursuit of robust hypotheses fuels scientific discovery and contributes to a deeper understanding of the world around us.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Who Is Liable When An Insured Suffers A Loss

Apr 02, 2025

-

The San Andreas Fault In California Is An Example Of

Apr 02, 2025

-

Which Of The Following Best Characterizes Ferromagnesian Silicates

Apr 02, 2025

-

The Last Common Ancestor Of All Animals Was Probably A

Apr 02, 2025

-

Identify The Stages Of Meiosis On The Diagram

Apr 02, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about What Are The Qualities Of A Good Hypothesis . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.