What In Broad Terms Is The Definition Of Deviance

Breaking News Today

Mar 20, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

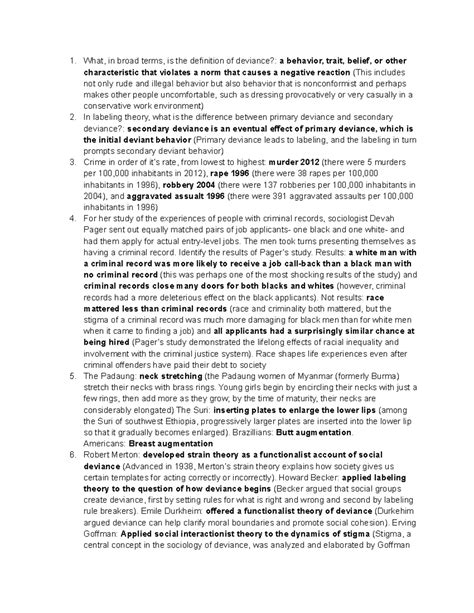

What, in Broad Terms, is the Definition of Deviance?

Deviance. The word itself conjures images of societal outliers, rebels, and rule-breakers. But what exactly is deviance? It's a concept far more nuanced and complex than a simple definition might suggest. Understanding deviance requires exploring its sociological underpinnings, the diverse perspectives surrounding its interpretation, and the ever-shifting boundaries that define what constitutes deviant behavior across different cultures and time periods.

Defining Deviance: A Multifaceted Concept

At its core, deviance refers to any behavior, belief, or condition that violates significant social norms in a given society or group. This seemingly straightforward definition immediately highlights its inherent relativity. What is considered deviant in one culture might be perfectly acceptable, even expected, in another. For example, public displays of affection may be frowned upon in some cultures while being commonplace in others. Similarly, certain religious practices that are perfectly acceptable within a specific religious community might be considered deviant by the broader society.

This relativity underscores the crucial role of social context in defining deviance. It's not an inherent quality of an act itself, but rather a social judgment applied to that act based on prevailing norms and values. This means that deviance is not static; it's constantly evolving as societal norms change over time. Behaviors once considered deviant may become accepted, and vice versa. Consider the changing attitudes towards homosexuality or women's roles in society – behaviors once widely condemned are now largely accepted in many parts of the world.

Beyond Actions: Beliefs and Conditions

It's important to emphasize that deviance isn't limited to actions. Deviant beliefs and deviant conditions also fall under this umbrella. Holding unconventional religious or political beliefs, for instance, can be categorized as deviant depending on the societal context. Similarly, certain physical or mental conditions, like visible tattoos or diagnosed mental illnesses, might be stigmatized and considered deviant despite being involuntary. The stigma associated with these conditions often leads to social exclusion and discrimination, highlighting the power of societal labeling in shaping perceptions of deviance.

Sociological Perspectives on Deviance

Several key sociological perspectives offer valuable insights into the nature and causes of deviance. These perspectives provide frameworks for understanding how deviance arises, how it's maintained, and how it impacts society.

1. Functionalist Perspective: Maintaining Social Order

Functionalist theorists, such as Émile Durkheim, view deviance as a necessary element of social order. They argue that deviance serves several crucial functions:

- Reinforcing social norms: By punishing deviants, society reaffirms its norms and values, reminding individuals of the consequences of nonconformity. This process strengthens social cohesion and stability.

- Promoting social change: Deviance can challenge existing social norms and spark social movements that lead to positive societal change. Civil rights activists, for example, were initially considered deviant for defying segregation laws, but their actions ultimately led to significant social progress.

- Identifying problems in society: High rates of deviance in certain areas might indicate underlying social problems, such as poverty, inequality, or lack of opportunity. Addressing these problems can contribute to a more functional society.

2. Conflict Perspective: Power and Inequality

Conflict theorists, influenced by the works of Karl Marx, emphasize the role of power and inequality in shaping definitions of deviance. They argue that dominant groups in society use their power to define what is considered deviant, often to maintain their own interests and control over resources. Laws and social norms, from this perspective, are not neutral but rather reflect the interests of those in power. Behaviors that challenge the established power structure are more likely to be labeled as deviant, regardless of their inherent harmfulness. This perspective highlights how deviance can be a form of resistance against inequality and oppression.

3. Symbolic Interactionist Perspective: Labeling and Social Construction

Symbolic interactionists focus on the process through which individuals come to be labeled as deviant. They emphasize the role of social interaction and interpretation in shaping perceptions of deviance. Key concepts include:

- Labeling theory: This theory argues that deviance is not inherent in an act but rather a consequence of how others label that act. Once an individual is labeled as deviant, it can become a self-fulfilling prophecy, leading them to further engage in deviant behavior.

- Stigma: This refers to the negative social consequences associated with being labeled as deviant. Stigma can lead to social exclusion, discrimination, and reduced opportunities.

- Social control: This encompasses the mechanisms used by society to regulate behavior and maintain social order. These mechanisms can range from informal sanctions, such as disapproval, to formal sanctions, like imprisonment.

Types of Deviance

Deviance encompasses a broad spectrum of behaviors, beliefs, and conditions. Some common types include:

- Crime: Acts that violate formal laws and are punishable by the legal system. This includes a wide range of offenses, from minor infractions to serious felonies.

- Substance abuse: The excessive use of drugs or alcohol, often resulting in negative consequences for the individual and society.

- Mental illness: Conditions that affect a person's thinking, feeling, or behavior, often leading to social stigma and discrimination.

- Sexual deviance: Behaviors that violate societal norms regarding sexual behavior, such as prostitution or certain forms of sexual expression.

- Political deviance: Acts that challenge the established political system, such as protesting or engaging in acts of civil disobedience.

- Corporate deviance: Illegal or unethical acts committed by corporations or their employees, often for financial gain.

- Religious deviance: Beliefs or practices that deviate from the dominant religious norms in a society.

Measuring Deviance

Measuring deviance presents significant challenges due to its subjective nature and the difficulty in capturing all forms of deviant behavior. However, several methods are used:

- Official statistics: Data collected by law enforcement agencies, such as crime statistics, provide information on certain types of deviance, but they often underrepresent the true extent of deviance due to underreporting and biases in reporting.

- Self-report studies: Surveys that ask individuals about their own deviant behaviors provide a more comprehensive picture, but they rely on respondents' honesty and can be subject to recall bias.

- Observation studies: Direct observation of behavior in natural settings can provide valuable insights, but it can be time-consuming and difficult to generalize findings.

The Social Construction of Deviance

The concept of social construction is central to understanding deviance. It highlights how our perceptions and definitions of deviance are shaped by social and cultural factors. What is considered deviant is not inherent in the act itself but is a product of social processes. This includes:

- Moral entrepreneurs: Individuals or groups who actively work to define certain behaviors as deviant and promote laws or social norms to regulate them.

- Media representations: The media plays a significant role in shaping public perceptions of deviance, often focusing on sensationalized or extreme cases that reinforce stereotypes and biases.

- Social interactions: Our interactions with others influence our understanding of what is considered normal or deviant.

Conclusion: Understanding the Fluidity of Deviance

Defining deviance is an ongoing process, constantly shaped by evolving social norms, power dynamics, and individual interpretations. While a simplistic definition might describe it as behavior violating significant social norms, the reality is far more complex. Understanding deviance requires a multi-faceted approach that incorporates sociological perspectives, recognizes the diverse forms deviance can take, and acknowledges the social construction of this fluid and ever-changing concept. It's a critical area of study for understanding societal dynamics, social control mechanisms, and the ongoing negotiation of acceptable behavior within any given society. The more we understand the intricacies of what society labels as 'deviant', the better equipped we are to foster more inclusive and just social environments.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

An Adversary With The And To Undertake Any Actions

Mar 21, 2025

-

Are Made Up Of Related Records

Mar 21, 2025

-

Cgl Always Excludes Liability Arises Out Of

Mar 21, 2025

-

How Are Ex Nihilo Stories Different From Earth Diver Stories

Mar 21, 2025

-

An Insured Status Under Social Security Can Be Described As

Mar 21, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about What In Broad Terms Is The Definition Of Deviance . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.