When Is A Covalent Bond Likely To Be Polar

Breaking News Today

Mar 20, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

When is a Covalent Bond Likely to Be Polar?

Covalent bonds, the fundamental forces holding atoms together in molecules, aren't always created equal. While they all involve the sharing of electrons between atoms, the degree of sharing can significantly vary, leading to a spectrum of bond polarities. Understanding when a covalent bond is likely to be polar is crucial in predicting molecular properties like solubility, boiling point, and reactivity. This comprehensive guide delves into the intricacies of polar covalent bonds, exploring the factors that influence their formation and highlighting practical applications of this concept in chemistry.

Understanding Electronegativity: The Driving Force Behind Polarity

The key to understanding polar covalent bonds lies in the concept of electronegativity. Electronegativity is a measure of an atom's ability to attract electrons towards itself within a chemical bond. Atoms with higher electronegativity exert a stronger pull on shared electrons, creating an uneven distribution of charge.

The Pauling Scale: Quantifying Electronegativity

Electronegativity isn't a directly measurable quantity; instead, it's a relative value. The most widely used scale is the Pauling scale, developed by Linus Pauling, where fluorine (the most electronegative element) is assigned a value of 4.0. Other elements are assigned values relative to fluorine. Elements on the right side of the periodic table (non-metals) generally have higher electronegativity than elements on the left (metals).

Electronegativity Differences and Bond Type

The difference in electronegativity (ΔEN) between two atoms involved in a covalent bond is crucial in determining the bond's polarity:

- ΔEN = 0: A nonpolar covalent bond is formed. This occurs when two identical atoms (e.g., O₂ in oxygen gas) share electrons equally.

- 0 < ΔEN < 1.7: A polar covalent bond is formed. The shared electrons are pulled more strongly towards the more electronegative atom, creating a partial negative charge (δ-) on that atom and a partial positive charge (δ+) on the less electronegative atom.

- ΔEN ≥ 1.7: An ionic bond is formed. The electronegativity difference is so large that one atom essentially takes the electron(s) from the other atom, resulting in the formation of ions (cations and anions) held together by electrostatic attraction.

It's important to note that the 1.7 value is not a strict cutoff; the distinction between polar covalent and ionic bonding can be blurry in some cases.

Factors Influencing Polar Covalent Bond Formation

Several factors contribute to the likelihood of a polar covalent bond forming:

1. Difference in Electronegativity: The Primary Factor

As stated earlier, the most significant factor determining the polarity of a covalent bond is the difference in electronegativity between the two atoms involved. A larger electronegativity difference leads to a more polar bond.

2. Bond Length: Influence on Electron Distribution

While electronegativity difference is the dominant factor, bond length also plays a role. Shorter bond lengths generally lead to a greater degree of electron sharing, potentially enhancing the effect of electronegativity differences. This is because the closer the atoms are, the stronger the electrostatic interaction between the nuclei and the shared electrons.

3. Molecular Geometry: Impact on Overall Dipole Moment

Even if individual bonds within a molecule are polar, the molecule as a whole might not exhibit a net dipole moment. Molecular geometry dictates how individual bond dipoles (vectors representing the direction and magnitude of bond polarity) add up. If the bond dipoles cancel each other out due to symmetry (e.g., CO₂), the molecule is considered nonpolar overall, despite having polar bonds.

4. Resonance: Electron Delocalization and Bond Polarity

In molecules exhibiting resonance, electrons are delocalized across multiple bonds, influencing the overall charge distribution. Resonance can affect bond polarity by either increasing or decreasing the polarity depending on the specific resonance structures involved. For example, in benzene, the delocalized electrons lead to a nonpolar molecule despite the presence of polar C-H bonds.

5. Inductive Effects: Influence from Neighboring Groups

In larger molecules, the presence of electronegative or electropositive groups can influence the polarity of nearby bonds. This is called the inductive effect. Electronegative groups can pull electron density away from adjacent bonds, making them more polar, while electropositive groups can have the opposite effect.

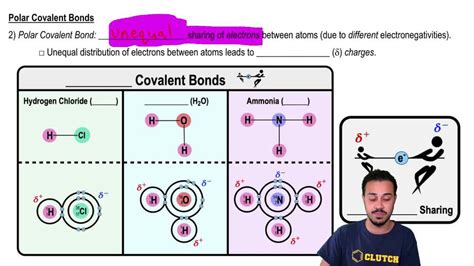

Examples of Polar Covalent Bonds

Let's examine some real-world examples to solidify our understanding:

1. Water (H₂O)

Water is a classic example of a molecule with polar covalent bonds. Oxygen (O) is significantly more electronegative than hydrogen (H). This results in a polar O-H bond, with the oxygen atom carrying a partial negative charge and the hydrogen atoms carrying partial positive charges. The bent molecular geometry of water ensures that the bond dipoles do not cancel each other out, resulting in a polar molecule overall.

2. Hydrogen Chloride (HCl)

Chlorine (Cl) is more electronegative than hydrogen (H). The H-Cl bond is polar covalent, with chlorine carrying a partial negative charge and hydrogen carrying a partial positive charge. The linear geometry of HCl ensures that the bond dipole is the overall molecular dipole.

3. Carbon Monoxide (CO)

Carbon monoxide displays a polar covalent bond despite the relatively small difference in electronegativity between carbon and oxygen. Oxygen is more electronegative, resulting in a partial negative charge on oxygen and a partial positive charge on carbon. The triple bond between carbon and oxygen enhances the polarity, and the linear geometry does not cancel out the dipoles.

4. Ammonia (NH₃)

Nitrogen is more electronegative than hydrogen, resulting in polar N-H bonds. The trigonal pyramidal geometry of ammonia prevents the bond dipoles from cancelling each other out, leaving the molecule polar overall.

5. Carbon Dioxide (CO₂)

Although the C=O bonds in carbon dioxide are polar (oxygen is more electronegative than carbon), the linear molecular geometry causes the bond dipoles to cancel each other out, resulting in a nonpolar molecule.

Implications of Polarity: Properties and Applications

The polarity of covalent bonds has profound implications for the physical and chemical properties of molecules, influencing many real-world applications:

1. Solubility: "Like Dissolves Like"

Polar molecules tend to dissolve well in polar solvents (like water), while nonpolar molecules dissolve better in nonpolar solvents (like oil). This principle of "like dissolves like" is essential in many chemical processes and in everyday life.

2. Boiling and Melting Points: Intermolecular Forces

Polar molecules exhibit stronger intermolecular forces (like dipole-dipole interactions and hydrogen bonding) than nonpolar molecules. These stronger interactions lead to higher boiling and melting points.

3. Reactivity: Electrophilicity and Nucleophilicity

Polar bonds create regions of partial positive and negative charges within a molecule, influencing its reactivity. The partially positive atom can act as an electrophile (electron-loving), while the partially negative atom can act as a nucleophile (nucleus-loving). This is fundamental in organic chemistry reaction mechanisms.

4. Spectroscopy: Identifying Polar Bonds

Techniques like infrared (IR) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy can be used to detect and characterize polar bonds within molecules based on their distinct spectral signatures.

5. Materials Science: Designing Polar Materials

Understanding bond polarity is critical in materials science for designing materials with specific properties. For instance, the polarity of certain polymers influences their flexibility, strength, and interaction with other materials.

Conclusion: A Deeper Understanding of Covalent Bond Polarity

Predicting the polarity of a covalent bond is a cornerstone of understanding molecular behavior. By considering electronegativity differences, bond length, molecular geometry, and other influencing factors, chemists can accurately predict and explain the properties of countless molecules. This knowledge extends into diverse fields, including drug design, materials science, and environmental chemistry, demonstrating the far-reaching impact of this fundamental concept. The ability to distinguish between polar and nonpolar bonds is a critical skill for any aspiring chemist or scientist engaging in molecular-level studies.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

What Does This Part Of The Soliloquy Reveal About Hamlet

Mar 21, 2025

-

Which Of The Following Does Not Improve Performance In Sports

Mar 21, 2025

-

If Neutral Atoms Become Positive Ions They

Mar 21, 2025

-

Transition Plans Are Required For Systems Being Subsumed

Mar 21, 2025

-

Once Entrance And Access To The Patient

Mar 21, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about When Is A Covalent Bond Likely To Be Polar . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.