How Is The Neutral Stimulus Related To The Cs

Breaking News Today

Mar 21, 2025 · 5 min read

Table of Contents

- How Is The Neutral Stimulus Related To The Cs

- Table of Contents

- How is the Neutral Stimulus Related to the CS? Understanding Classical Conditioning

- The Foundation of Classical Conditioning: Pavlov's Dog

- The Transformation: From NS to CS

- The Role of Prediction and Expectation

- Extinction and Spontaneous Recovery: The Dynamic Nature of the CS

- Generalization and Discrimination: Refining the CS-CR Relationship

- Higher-Order Conditioning: Building upon the CS

- Real-World Applications of the NS-CS Relationship

- Conclusion: The Dynamic Dance of the NS and CS

- Latest Posts

- Latest Posts

- Related Post

How is the Neutral Stimulus Related to the CS? Understanding Classical Conditioning

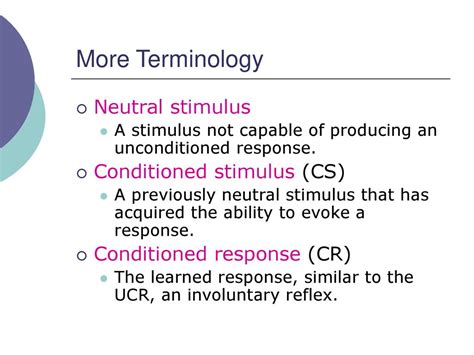

Classical conditioning, a fundamental concept in learning and behavior, hinges on the relationship between a neutral stimulus (NS) and a conditioned stimulus (CS). Understanding this relationship is key to grasping the entire process. This article will delve deep into how the neutral stimulus transforms into the conditioned stimulus, exploring the underlying mechanisms and providing real-world examples to solidify your understanding.

The Foundation of Classical Conditioning: Pavlov's Dog

Before diving into the intricacies, let's revisit the foundational experiment: Pavlov's dogs. Ivan Pavlov, a renowned physiologist, inadvertently discovered classical conditioning while studying canine digestion. He noticed that dogs would salivate not only at the sight of food (an unconditioned stimulus, or UCS, eliciting an unconditioned response, or UCR – salivation), but also at the sight or sound of the person who usually fed them. This seemingly insignificant observation revolutionized our understanding of learning.

Pavlov systematically investigated this phenomenon. He paired a neutral stimulus (e.g., a bell) with the unconditioned stimulus (food). Initially, the bell (NS) elicited no salivary response. However, after repeated pairings of the bell and food, the dogs began salivating at the sound of the bell alone. The bell had transitioned from a neutral stimulus to a conditioned stimulus (CS), eliciting a conditioned response (CR) – salivation – similar to the original UCR.

The Transformation: From NS to CS

The crucial element here is the repeated pairing of the NS and UCS. This is not a passive association; it's an active learning process. The brain actively establishes a connection between the previously neutral stimulus and the unconditioned stimulus through synaptic changes and the strengthening of neural pathways. This process is known as acquisition.

The strength of the association between the NS and the UCS heavily influences the speed and strength of the conditioning. Factors influencing the acquisition phase include:

- Contingency: The reliability with which the NS predicts the UCS. A consistently paired NS and UCS lead to faster conditioning than an inconsistently paired one.

- Contiguity: The proximity in time between the NS and UCS. The shorter the interval, generally the stronger the association. However, the optimal interval varies depending on the stimuli involved.

- Intensity: The salience of both the NS and UCS. More intense stimuli are generally more easily associated. A loud bell is likely to become a CS faster than a faint one.

- Biological preparedness: Some associations are easier to learn than others. This relates to our evolutionary history; we're predisposed to learn certain associations more readily than others due to survival advantages. For example, associating nausea with a specific food is often easier than associating a light with a shock.

The Role of Prediction and Expectation

The key to the NS-to-CS transformation is prediction. The NS becomes a predictor of the UCS. The animal learns to associate the NS with the impending arrival of the UCS, anticipating the UCR. This anticipatory response is the hallmark of classical conditioning. The animal isn't just reacting to the stimulus; it's actively predicting and preparing for the subsequent event.

Extinction and Spontaneous Recovery: The Dynamic Nature of the CS

The relationship between the NS and CS isn't static. If the CS (e.g., the bell) is repeatedly presented without the UCS (food), the conditioned response (salivation) will gradually weaken and eventually disappear. This is known as extinction. It doesn't mean the association is completely erased; it's just suppressed.

Interestingly, after a period of extinction, if the CS is presented again, the CR may spontaneously reappear, albeit weaker than before. This is called spontaneous recovery. This demonstrates the persistence of the learned association even after it appears to have been extinguished.

Generalization and Discrimination: Refining the CS-CR Relationship

Classical conditioning isn't limited to a single specific stimulus. Stimulus generalization occurs when a similar stimulus to the CS elicits a similar CR. For example, if a dog is conditioned to salivate to a specific tone, it might also salivate to slightly different tones. The similarity of the stimulus to the original CS determines the strength of the generalized response.

Conversely, stimulus discrimination involves learning to differentiate between the CS and other similar stimuli. Through differential reinforcement (rewarding responses to the CS and not rewarding responses to similar stimuli), the animal learns to respond selectively to the original CS.

Higher-Order Conditioning: Building upon the CS

Once a CS is established, it can be used to condition another neutral stimulus. This is called higher-order conditioning. For example, if a light is repeatedly paired with the bell (which is already a CS for salivation), the light itself might eventually elicit salivation. However, higher-order conditioning is generally weaker than first-order conditioning.

Real-World Applications of the NS-CS Relationship

The transformation of a neutral stimulus into a conditioned stimulus has profound implications across numerous aspects of human life and beyond:

- Phobias: Phobias often develop through classical conditioning. A neutral stimulus (e.g., a dog) becomes associated with a negative experience (e.g., a dog bite), transforming the NS into a CS that elicits fear.

- Taste aversion: A single pairing of a novel food (NS) with illness (UCS) can lead to a strong aversion to that food (CS). This is a powerful example of biological preparedness.

- Advertising: Advertisers often pair their products (NS) with positive stimuli (UCS, e.g., attractive people, beautiful scenery) to create positive associations with their products (CS).

- Drug addiction: Environmental cues (NS) associated with drug use (UCS) can become conditioned stimuli that trigger cravings (CR). This is a significant factor in relapse.

- Therapeutic applications: Techniques like systematic desensitization and aversion therapy utilize the principles of classical conditioning to treat phobias and other behavioral problems.

Conclusion: The Dynamic Dance of the NS and CS

The relationship between the neutral stimulus and the conditioned stimulus is the cornerstone of classical conditioning. The transformation of the NS into a CS is a dynamic process, influenced by various factors such as contingency, contiguity, and biological preparedness. Understanding this relationship is crucial for comprehending how learning occurs and how we can utilize this knowledge to understand and modify behavior. The power of association, the predictive nature of the CS, and the ongoing interplay between extinction and spontaneous recovery highlight the complexity and fascinating nature of this fundamental learning mechanism. From phobias to advertising, the principles of classical conditioning have far-reaching implications in our understanding of the world around us.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Figurative Language In Romeo And Juliet Quizlet

Mar 23, 2025

-

Texas Cybersecurity Awareness For Employees Program Quizlet

Mar 23, 2025

-

What Is A Certificate Of Insurance Quizlet

Mar 23, 2025

-

The Core Of The Sun Is Quizlet

Mar 23, 2025

-

How Are Stress And Physical Health Related Quizlet

Mar 23, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about How Is The Neutral Stimulus Related To The Cs . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.